Being just 40 miles from home this seemed worth doing today. I had seen the Nearctic wader in question just once before, a little distantly at Bournemouth’s Longham Lakes in Sep 2012, so it hasn’t featured in this journal until now. My recollections of that occasion are vague, so having been told the new bird was easier to view I went to take a look.

White-rumped Sandpiper is one of the more regular Nearctic vagrants of its group to occur in the British Isles, with several records through each autumn passage. In July 2022 there had been sightings at Snettisham and Titchwell in Norfolk, Lodmoor in Dorset and three Scottish sites prior to a quite confiding individual turning up on the Berks / Bucks border during Thursday (21st). This wader breeds on the Arctic tundra from June to August, and return migration to the estuaries of southern South America spans July to early December with juveniles going last.

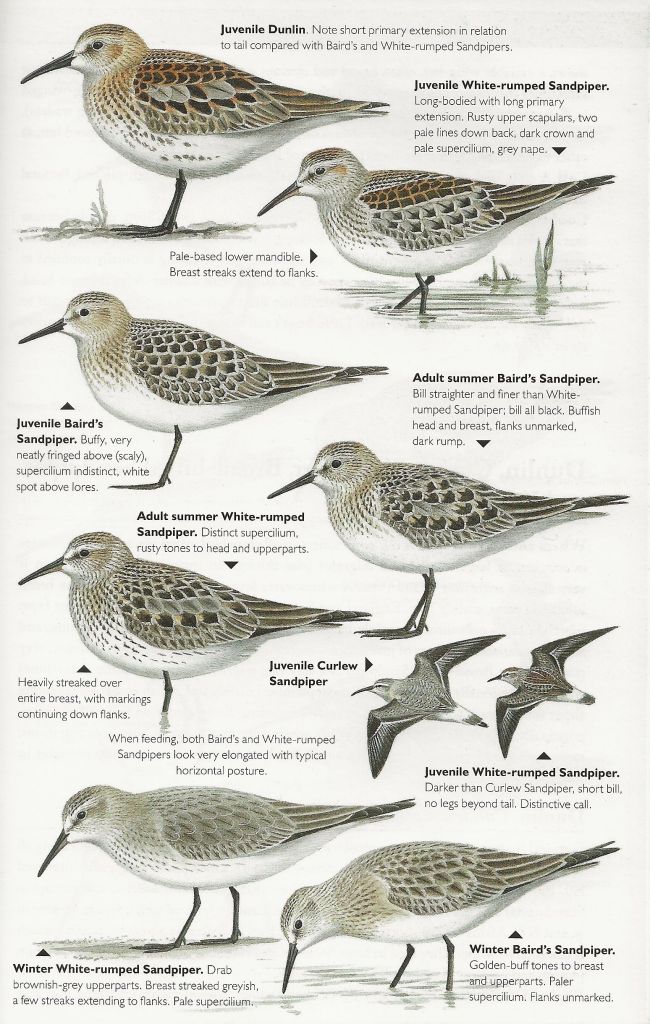

By comparison with what I regard as my default small wader Dunlin, White-rumped and the similar Baird’s Sandpipers are a little smaller. The two share a slimmer, longer-bodied and shorter-legged profile with remarkably long primary projections; the last-named feature meaning the wing-tips extend beyond the tail. After the white upper tail of its name, White-rumped’s other stand-out diagnostic is cited as a distinct whitish supercilium (eye stripe), while adults such as today’s bird display rusty tones to the head and upperparts. A weakish wing bar is apparent in flight. The graphic below presents full plumage topography for all three waders mentioned in this paragraph.

I arrived at the flat and featureless Dorney Common (SU942789) at 9:20am to find a dozen or more birders watching my quest, and was put onto it straight away. I had been here twice previously to log my second Pectoral Sandpiper (Sep 2012) and a Spotted Crake (Sep 2018 – see here), both of which had been quite difficult to view on an adjacent wetland.

The White-rumped Sandpiper was showing really well on a shallow flash in the common’s north-east corner (pictured below) that was populated by gulls, geese and just three transient waders. That feature still seemed remarkably muddy and watery in its scorched surroundings considering this past week’s exceptionally hot weather in which Great Britain had recorded temperatures of 40 deg C for the first time ever.

By comparison with my experience in Bournemouth almost 10 years ago, today was far more instructive as the bird was near enough for all the diagnostic features to be plain to discern. It also remained in close proximity with a plump and much darker-toned Dunlin for much of the time (pictured below). Its feeding action was generally quite brisk, though at times it appeared to move more inconspicuously. Using my digiscoping attachment I was also able to obtain the poor quality pictorial records of this post.

So my hour on-site here imparted a complete education in identifying WRS. As with last year’s Western Sandpiper (see here) and Long-toed Stint (see here) this had been another exercise in witnessing just how distinct these vagrant “peeps” are from one another on profile and jizz if only they are observed well enough. With the cost of petrol and health issues having impacted my birding so far this year, the twitchette of this post has been a very welcome diversion. This post’s featured bird departed overnight.