The only English Aroid enjoys a place in national folklore like few other native wild plants. Having been unable to resist the little irony at the close of my previous post, I soon began to notice imminent Cuckoo Pint blooms in those unkempt corners of my garden that I retain at least partly for their benefit. Everywhere I have walked in the local countryside so far this year there has been a profusion of Arum maculatum foliage. Now these rampant, quintessentially English plants of shady places everywhere are revealing their very particular character.

“Lords and Ladies” in Toot Baldon, Oxon

Thus having searched on-line for whatever mildly entertaining trivia might be forthcoming, I now present it herein. Folk-tales and herbal remedies a-plenty have been associated with the Cuckoo Pint over the centuries. Estimates of the number of other colloquial names for it range from 90 to upwards of 150, more than any other native English plant. Many of them and especially the gender-related ones arise from the brief April bloom’s suggestive quality. Consider: Lords and Ladies, Cows and Bulls, Stallions and Mares, Devils and Angels, Adam and Eve, Soldiers Diddies, or most to the point the Willy Lily.

So what’s in a name? I was possibly slow to realise, until researching this piece, that if all but the first two and last two letters of “Cuckoo Pint” are removed … I’ll stop there. So perhaps the term is a quaint folklore equivalent of rhyming slang, or similar play on words, but I have yet to find anything else on-line which is so impolite as to confirm that. Moving swiftly on, if not merely a euphemism the “Cuckoo” half of the name may refer to the time of year when both those birds and the Arum blooms first appear in the countryside. “Pint” is widely agreed to be a shortening of the old-English word “Pintle” meaning … well, can you guess? “Priest’s Pintle” is yet another of the vernacular names

But the wild Arum known as “Cuckoo Pint” possessed an ability to stir the rustic English imagination in more diverse ways. Beholders of the inflorescence who might prefer religious interpretations may choose from Friar’s Cowl, Jack in the Pulpit, or Parson and Clerk. Other non-smutty alternatives might be Soldier in a Sentry Box, Bloody Man’s Finger, Wake Robin, Tender Ear, Cheese and Toast, and many more besides. Two of the longer winded ones are “Sonsie Give Us Your Hand” or even “Kitty Come Down the Lane, Jump Up and Kiss Me”; or so my researches suggest.

Cuckoo Pints around Toot and Marsh Baldon, Oxon

Given it’s more obvious amorous associations it is hardly surprising that historically the Cuckoo Pint has enjoyed a reputation for possessing aphrodisiac powers. Any country names with “Cuckoo” in them tend to have such meanings. A PDF published by Fareham Borough Council in 2019 (see here) states that in some areas it was believed girls could get pregnant simply by looking at this plant, yes really! Well there’s an excuse for frolicsome wenches of the day. I wonder if anyone believed them?

More credibly, this plant has been put to an astonishing range of uses over the centuries. In folk medicine the leaves of A maculatum were squeezed to extract the juice that was then used to burn off warts and other growths on the skin. This practice was particularly popular during the mid-17th century. The roots of the plant were also dried and made into a powder, used to alleviate rheumatism or paralysis. In the 18th century, the leaf juice was distilled and applied to the face as an anti-ageing treatment; while that of the root was applied to treating asthma, ruptures, scurvy and wind. Herbalists largely stopped using it at the start of the 20th century.

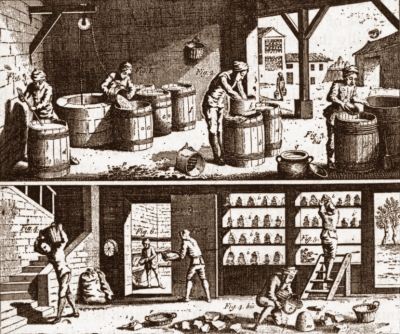

17th century starch makers

Away from “medicine”, it was noted that root tubers contained starch that during the Elizabethan period was used to stiffen linen, especially the then fashionable long ruffs (collars). The 15th century nuns of Syon Abbey used the roots to make starch for altar cloths and other church linens. Hence “Starchwort” was then yet another colloquial name. But due to the high corrosive properties of the juice, these practices didn’t last as people tasked with laundering the clothing could suffer painful effects.

“The most pure and white starch is made of the rootes of the Cuckoo-pint, but most hurtful for the hands of the laundresse that have the handling of it, for it chappeth, blistereth, and maketh the hands rough and rugged and withall smarting”.

Gerard’s Herbal, 1633

All parts of the plant may produce allergic skin reactions. But there are nonetheless reports in past published herbals of Arum starch being used in skin cosmetics in 19th century Paris, and also for removing freckles in Italy at that time. An ointment made by stewing the juice of fresh sliced tubers with lard was in places cited as an efficient cure for the fungal skin infection Ringworm, despite causing blistering when applied.

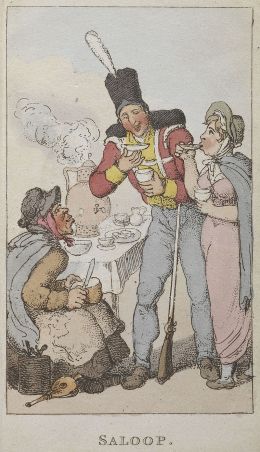

Cuckoo-pint root if washed and roasted well is edible, and when ground was once traded under the name of “Portland Sago”. This flour was used to make “Saloop”, a hot drink popular amongst the lower orders of 18th and 19th century society as a lower-cost alternative to tea or coffee. It was said to be very refreshing, and was served in the same way with milk and sugar, but if prepared incorrectly could be highly toxic. The beverage was also considered a remedy for various ailments as well as hangovers. But its popularity is said to have declined on becoming associated with treating venereal disease, after which drinking it in public was deemed shameful. Saloop street vendors in London then became replaced by coffee stalls.

Moving on to botanic matters the glossy, spear-shaped leaves appear very early in the year, followed by the blooms at this time of writing. Pollinators are attracted by an odour and raised temperature generated in the early evening. Minute flies visiting the plant enter the floral trap of the spathe through a zone of bristles, then fall into a smooth-walled floral chamber from which they cannot escape. Gorging themselves on a secretion produced by the female flowers at the base of the spadix, the trapped flies effect cross-pollination if they have previously visited another Cuckoo Pint. All the while the male flowers, situated much higher on the spadix, rain pollen down onto their guests. The next day, when smell, heat, and food are gone, those pollen-laden insects are allowed to escape by a wilting of the bristles. Thus released they are then as often as not recaptured by other inflorescences still in the smelly receptive stage, and so things continue.

As with many Aroids the blooms last for little more than a day, then the whole plant quickly wilts. Later in the season the stems turn into erect spikes of bright orange berries that are a highly attractive and long lasting feature wherever Cuckoo Pints occur. But as always in nature such a colouration indicates that the fruit is toxic if eaten. Doing so causes irritation in the mouth and throat, leading to swelling and pain and can affect breathing. Though that is not strictly poisonous, places where this post’s pictures were taken are best avoided by dog walkers, and children should be warned against touching the fruits.

Arum maculatum fruit in my garden (undated)

There is some variation in form between different wild Arums I am encountering around the Baldons on my Oxon green belt patch walks. The cream-coloured spadices of these ghostly, quasi-religious looking plants (below, top row), captured at dusk suggest a degree of hybridisation, being more like those of the continental Arum italicum than our own A maculatum. The former is grown in gardens such as my own, so maybe those aforementioned pollinators are ranging more widely. Some leaves also display a brown-blotched appearance, and in one case even the spathe (below, bottom).

Cuckoo Pints are always invasive. It is one of the wild plants that persist in my garden – like Bluebells, Euphorbia, Lily of the Valley and the ubiquitous Celandines – that however much I might try to reduce them are always back in force the following spring. Wild Arums are not robust, so if growth is removed after flowering there will be no visible trace through summer, autumn and early winter. Then new glossy green foliage will issue from the soil again as the end of winter beckons a new spring season and the renewed life then forthcoming.

Cuckoo Pints in a neglected corner of my garden

Now is the time to see and enjoy the sole English Aroid in bloom in our countryside, and if sought out there are plenty of them to be found. But these suggestive, evocative, even haunting symbols of simpler past ages and pleasures, that have been held in popular fascination for so long are in themselves far more transient. What thing of such strange, alluring beauty does not have the right to be so? Such is the mystery of Aroids and such, perhaps is life.

Thankyou for a most enjoyable and informative read. Beautiful!

LikeLike