Continuing with the Amanita theme of this journal’s autumn fungi content, The Blusher of the previous post has a number of quite similar, commonly occurring relatives of which we located two today. For foragers some care is required in distinguishing between the group, since those featured herein are not exactly good to eat, and for myself comparing all three has provided a further valuable mycology lesson.

Panther Cap (Amanita pantherina – pictured above) has a quite variably-toned, ochre-brown cap covered in pure white “universal veil fragments”, a mycological term referring to the membranous veil that encloses new fruits when they first emerge. As the fruit body grows and evolves in shape part of that veil turns into the pale cap warts exhibited by all the Amanitae I have featured so far. The remainder accumulates around the slightly swollen stem base as in the right hand specimen in the lead picture, just above which are two concentric rings known as a “volva”.

The 5 – 12 cm cap is once again domed at first but may flatten as the fruit matures. The stem ranges from 6 – 12cm in height and the gills are white. The left hand specimen in the picture above has a well developed upper stem collar that itself forms from the remnants of a second “partial veil” that covers the gills of immature fruits. A quite scarce mushroom in the British Isles, this Amanita grows in association with Beech as at today’s site, Oak or less often other hardwood trees. It is poisonous, containing toxins similar to those in the Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria – see here).

Grey Spotted Amanita (Amanita excelsa) is said to be rather more common than Panther Cap, but today we found just one small clump compared to two sprawling groups of the latter. The fallen fruits in the pictures below were already in very poor condition and needed to be propped up to capture the images, but I believe they show enough to clinch the ID. In this species the universal veil fragments are described as being grey, compared to the purer white of A pantherina, so unless the pictured specimens are infested with a white mould I believe they are diagnostic enough to clinch the ID. As always I am open to experienced guidance if I am wrong.

This Amanita grows in association with both hardwood and softwood trees and is often most abundant near the edge of mixed woodland where it fruits between July and November. The 8 – 15cm diameter, brown or grey-brown cap is initially domed, becoming almost flat or occasionally slightly concave at maturity. The stem, from 8 – 12cm long and 1.5 – 2.5cm in diameter, shares the swollen base of A pantherina but not the latter’s diagnostic volva.

Grey Spotted Amanita (all pictures)

Out of all British and European mushrooms and toadstools, the Amanitae are possibly some of the most recognizable and stately, and so a fitting genera with which to progress from my initial fascination with Magpie and Shaggy Inkcaps. There are 50 members of the former, of which about 15 may be considered widespread. For a guide to separating the entire genus see here.

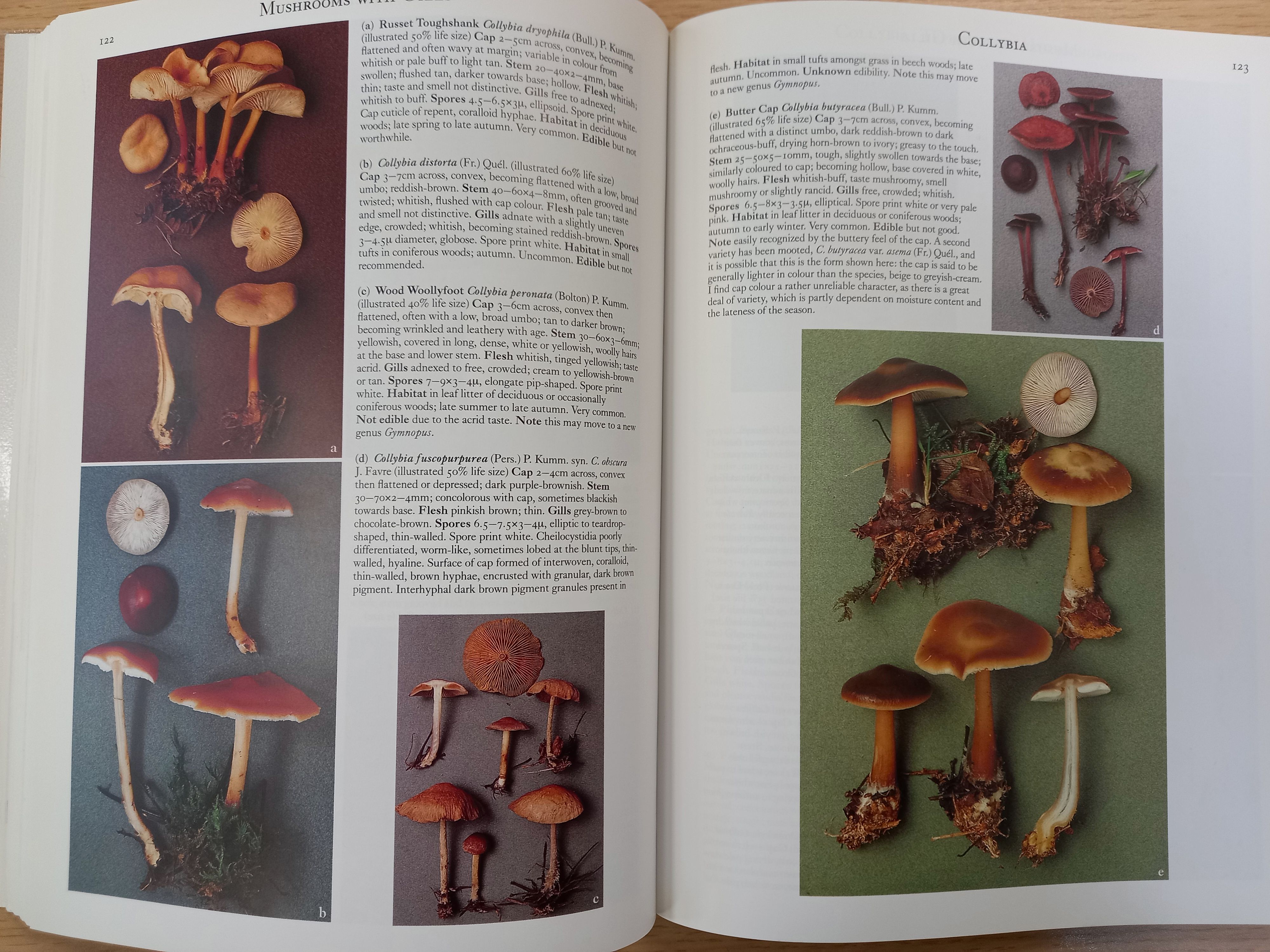

I returned to this same site a day later to attempt to locate more of the two species featured above, but without success. Wherever I trod, apart from the ubiquitous and bland Russet Toughshanks, Butter Caps and declining Clouded Funnels, I seemed to find mostly the ruined states of various other mostly unidentifiable mushrooms. Concluding that this autumn’s fungi season must now have peaked, I resolved to if possible keeps things going for another week then settle down to the mid-winter project that making further sense out of all this could become.

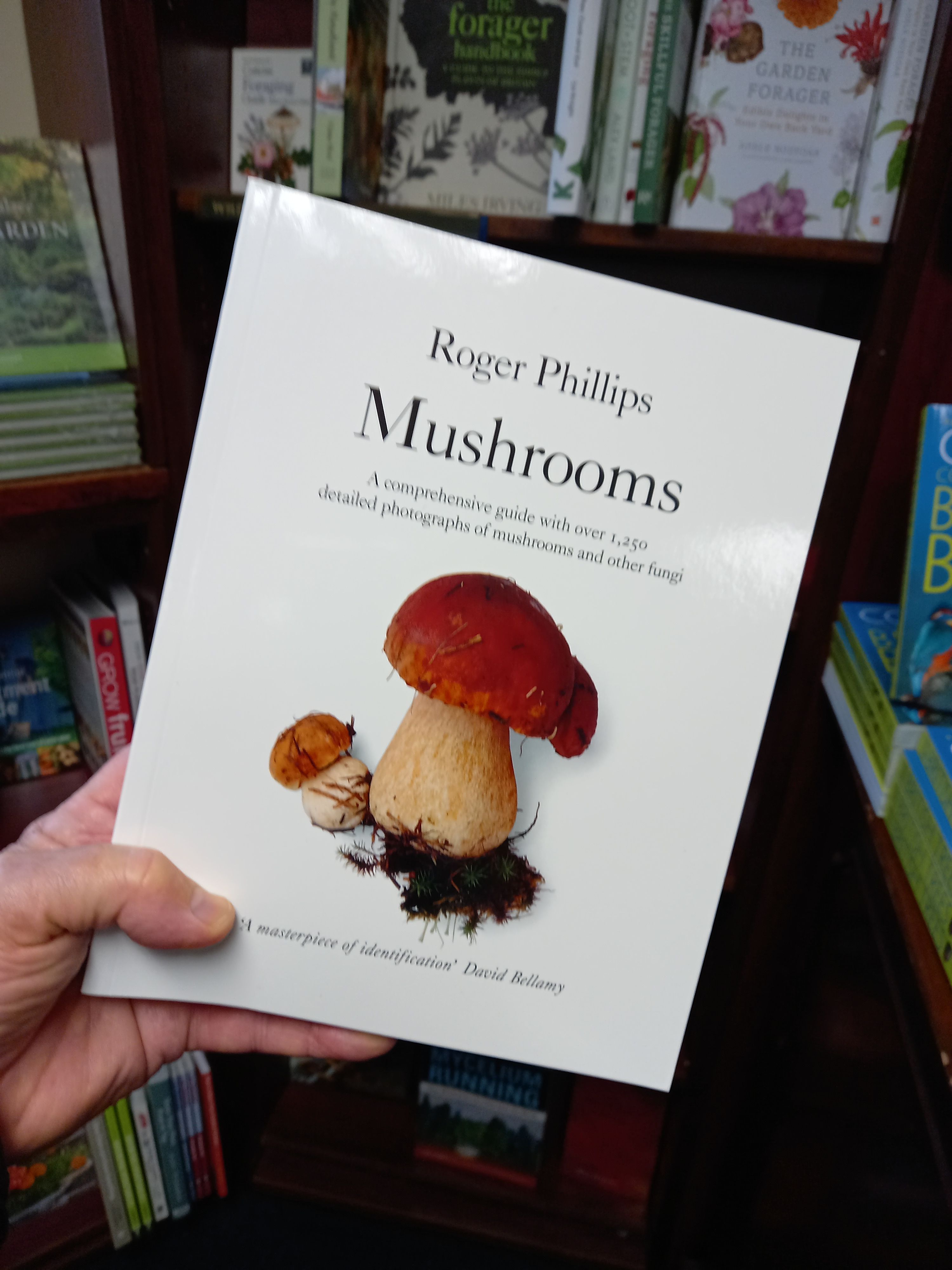

To that end I have now invested in a copy of the most excellent reference book pictured above. In working through and attempting to ID the many fungi images I have collected in the field over the past six weeks, it became clear that only a field guide illustrating all of the forms through each fruiting body’s cycle could be considered adequate. That seemed like a monumental task, I wondered if such a work existed and indeed it does. As first published in it’s present format by Macmillan in 2006, this volume represented the culmination of 30 years work by the now 89-year old author Roger Philips, assisted by other leading British mycology authorities.

In that time some 35,000 specimens of 1250 species were collected and photographed under studio conditions, as exemplified by the pages illustrating Russet Toughshank and Butter Cap (above right). By comparison, photographic field guides as with birds, insects or other wildlife typically contain just one or two representations of each species that so often may be difficult to match to actual observations in the field. This book also uses common, not just Latin names and is written to present a simple and concise rather than learned level of detail. So to any other newly enthused fungi freak such as myself I would strongly recommend buying it (see here).