I will admit to a peculiar fascination with Helicodiceros muscivorus and apparently am not alone in that. The review article herein (see here) published upon the acquisition in 2020 of a “two-year from flowering” tuber for my own Aroid collection has now passed 500 referrals to reach the top 20 most popular Rn’S posts. But disappointingly that item did not bloom on schedule last season and has yet to make any growth this time around. If at all the tuber is shrinking rather than putting on bulk.

Hence my concern to check out the plants at UOBG again this year. When I first viewed these a little under 12 months ago (see here) the most mature specimen was past its best and two smaller ones had already gone over, so this year I timed things a little earlier in April than then. Great Britain’s longest established scientific gardens lie just across the road from Magdalen College, so on 13th I combined the post before last’s visit there with this.

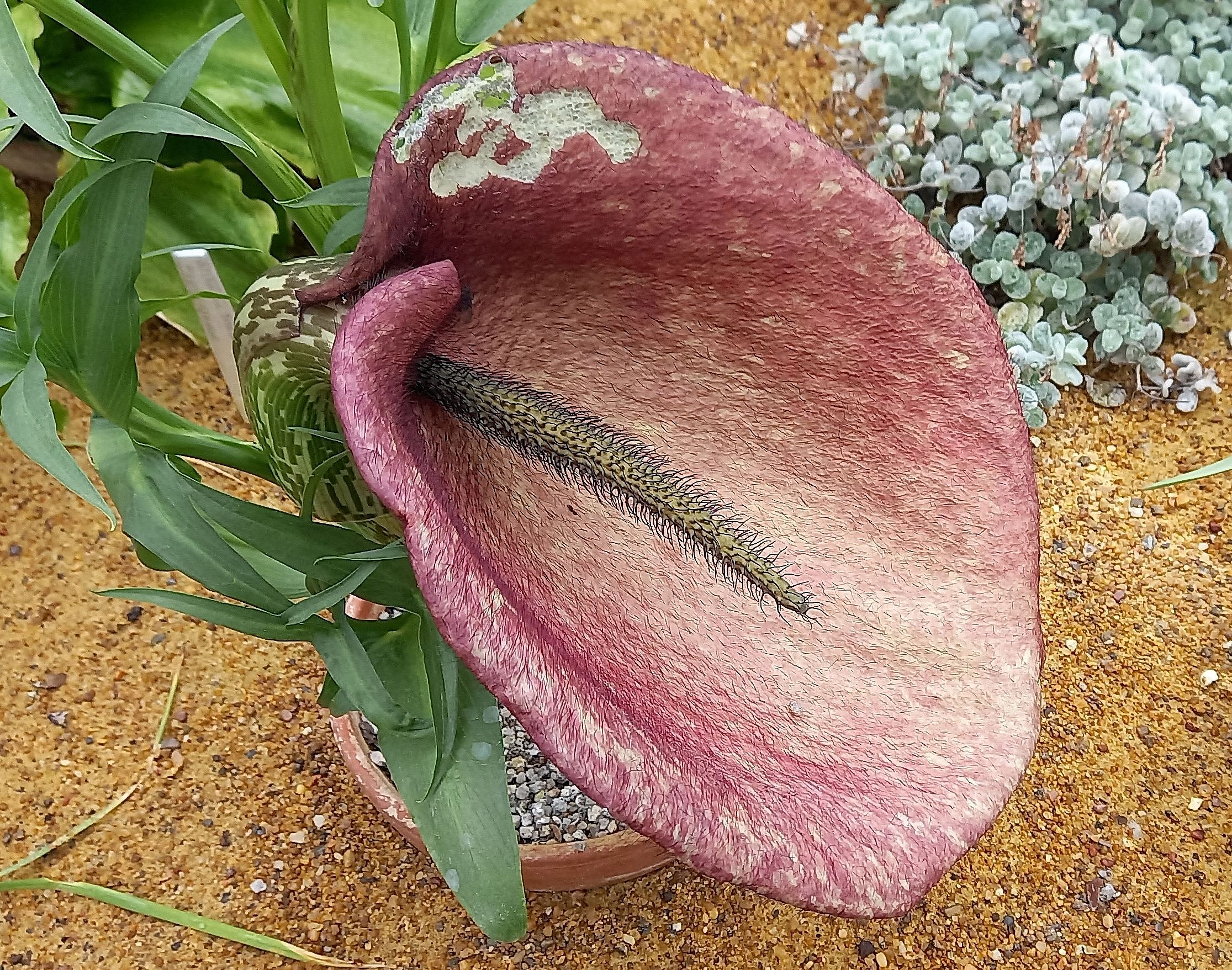

Heliodiceros muscivorous, the “Dead Horse Arum”

In the same glasshouse where I saw the Helicos last year there were two developing specimens. Just look at that bulging, ripe inflorescence (above left) and feel the sense of anticipation mingled with imminent danger as it prepares to unleash its magnificence and malodour upon the world. I had clearly timed things better this season and the plant could not be far from blooming. So it was now a matter of coming back on each available day until the event could be witnessed.

This took several more visits to achieve. Through four checks in five days the following week the inflorescence grew ever more plump and expectant looking but appeared to be in no hurry. By Friday (21st) the spadix was beginning to unfurl (below right), while a third plant had been put out in the glasshouse (left). Would sod’s law dictate that the blooming event I was tracking so patiently might materialise over my working weekend?

Today (Monday 24th) I hoped the wait would be over. Walking across Magdalen Bridge one more time I looked to see if the door to the glasshouse was open, suggesting there might be a bit of a pong inside? The object of my dedicated attention is of course reputed to be one of the world’s 10 foulest smelling plants. But the door was closed and within the largest Helico (pictured below) was beyond the pristine state in which I had hoped to record it. The spadix must indeed have opened over the weekend, probably on Saturday morning (22nd) as there was some damage to it and the infamous “Dead Horse Arum” odour was barely detectable. But a mission of 12 days had now been accomplished.

What’s been nibbling at and spoiling this then? There were two more plants here to attempt to connect with on their first day of flowering, so I went back on Thursday 11th May after my week in Greece (see next three posts). The smaller plant was in full bloom though the spadix had also suffered damage (below left), and an odour was detectable. To me this was no more intense than from other Aroids I have grown at home, but the flies were loving it. The larger plant (right) appeared to have gone over, the closed spadix becoming even more suggestive looking in the process.

So the Helico blooming season at UOBG had now almost run its course. When I got home I checked my own 2020 FS2 purchase that prompted this series herein, and the tuber was still firm but doing very little. The pictures in this post were all taken with my phone, which proved a better solution inside a glasshouse and often against the light.