There is nothing I can really add to what has already been published online about this bird. So here I will merely recount my own day spent catching up with what is possibly Great Britain’s most popular rarity of 2021. Since his arrival there on 28th June the seasoned Black-browed Albatross commonly known as “Albert” has drawn thousands of admirers, both birders and general public to RSPB Bempton Cliffs in Yorkshire. I have waited for an opportunity to observe him without driving beyond my preferred range, and that came today.

Arriving on-site (TA 197739) at 6am, in company with Ewan and his regular long-distance twitching buddy Mark, we headed out to the Staple Nook viewpoint. There Albert likes to wile away his time loafing amongst the breeding Gannets before putting on impressive flight displays when the mood takes him. Between them my day’s 500+ British list colleagues have successfully converted almost every new national mega of recent years, including this one twice before, so I had chosen my carriers consciously. On taking up position with something-teen other early birders we learned our quest had flown in to the cliff face around 20 minutes previously, but was now out of sight somewhere below us all.

Cue a wait for the show to commence … quite a time as things transpired. The longest I have ever waited for a bird to take the stage was seven hours for a Baillon’s Crake at Rainham Marsh, Essex in September 2012. Then I concluded that other lifer must have been a female exercising her prerogatives. Being a chap, the reputed half-centurion Albert really ought to have known better. He has not been noted for spending such lazy mornings as today too often, but local birders around me said his routine is never predictable. And so we waited for flight to commence … on and patiently on.

After three hours word came through that Albert was visible on the cliffs from 500 metres or so away to our right, where some birders had picked him out. This being a lifer for me but not my two colleagues, I went over while they stayed behind. I was put onto a rather indistinct grey form nestled amongst the Gannets someway down the sharp top edge from the viewpoint I had vacated, that I was assured was Albert’s back. Eventually this blob raised the white head and pink bill of the Black-browed Albatross I had seen so many images of online, while he alternately dozed and preened. So I thus added this nationally famous mega rarity to my life list … first priority achieved!

Returning to the Staple Nook viewpoint in relaxed mode I then chatted to other birders and friendly volunteer wardens around me, while Albert lazed his time away below and, yes upon checking quite definitely out of sight. Three more hours on at 12:18 the shout at last went up as the BBA got his act together and headed out to sea, landing on the water’s surface. At this stage I was informed by a regular local birder standing nearby this was what he usually does on first taking flight, and he was likely to fly inshore again soon. And so it transpired.

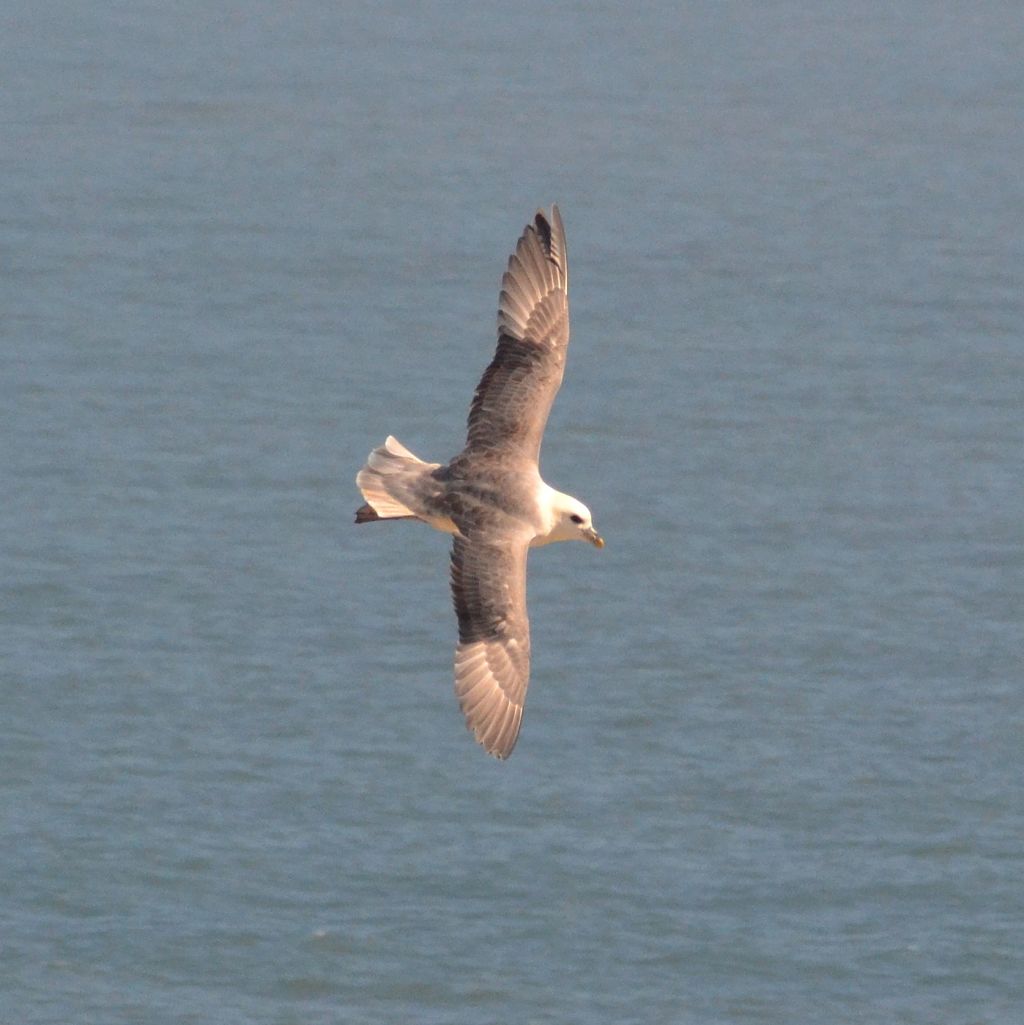

Cue an eventual aerial display that had my trip’s new colleague and ace photographer Mark Rayment enthusing for the rest of the day. Over the next 20 minutes or so Albert performed to his adoring audience like we had all been waiting to see, gliding around and banking on those huge outstretched wings. First out to sea, then close in to the cliff face, out of sight away to the left and around all over again. Since that early arrival here I had been assured this was what the bird would sooner or later do.

Though I will not be entering any of them into competitions, I am frankly astounded at having gained such half-decent images of my own for this post. With my ancient “photographic” artefact these were as usual achieved through altering the basic settings as I went along and hoping for the best. Mark told me the underside studies are the most difficult to achieve, and were the main reason he had wanted to come here again today.

Thus sated the by then hungry and thirsty gathering at Staple Nook mostly dispersed, the three of us included. It being just past midday on a bank holiday weekend, lots of general public who all seemed to know about the Albatross had joined the earlier birders on the cliff top to enjoy his eventual flight spectacular. My own party had a second mission for this day, a mega-rare Asian Plover, White-tailed Lapwing also in Yorkshire around 90 tortuous local driving minutes to the south. And so we went on our way.

Through our seven hour sojourn here we of course had the spectacle of Great Britain’s largest mainland Gannetry to keep us entertained. My best pictures of the morning are presented below. Though the other breeding seabirds have now dispersed, small numbers of Guillemot, Kittiwake and Shag were still active offshore. This was also the first occasion on which I have managed to capture Fulmar pictorially, and at one point two Porpoises swam past.

For the record, the Black-browed Albatross, whose home range is the oceans of the southern hemisphere, is thought to be the same individual that has wandered the North and Baltic Seas visiting coasts in Germany, Scandinavia and Great Britain since the 1960’s. No spring chicken now, Albert is likewise thought to be the only one of his kind in European waters and might survive for another 15 years into his seventies as this species often does.

If indeed the same bird he first visited Bempton Cliffs in 2014, then again in 2017 and 2020 always briefly, but this summer has been more or less a fixture for almost nine weeks. Though eternally lost throughout his long life to date, he must clearly feel very much at home here and I feel glad to have belatedly made his acquaintance on this day.