“I’m here to see the duck.” Whenever I responded thus as to why I was there, local people all knew what I meant, most having suspected it anyway. It seems that everyone on Texel is aware of the great avian celebrity in their midst, and are a little in awe at the low season boost to the island’s hospitality trade it is causing. Now, on a holiday-paid weekend off from work with a fair weather forecast, I myself had joined the prior flow of more than 10,000 visitors from across the continent and beyond on what is being described as Europe’s biggest ever twitch.

On 13th January news broke of a near-adult (third winter) drake Spectacled Eider amongst a wintering flock of Common Eider off the east coast of the first Friesian island of Texel (see here). This high-Arctic species normally winters in the Bering Sea between Alaska and Russia, and is very difficult to connect with even in its restricted home range. So the freak occurrence in Holland is most likely a lifetime’s opportunity for any European birder. On the evidence of my own visit recounted herein, interest is unlikely to wane any time soon, and there seems little reason for the bird to move on before the spring. Will it ever get home, who knows?

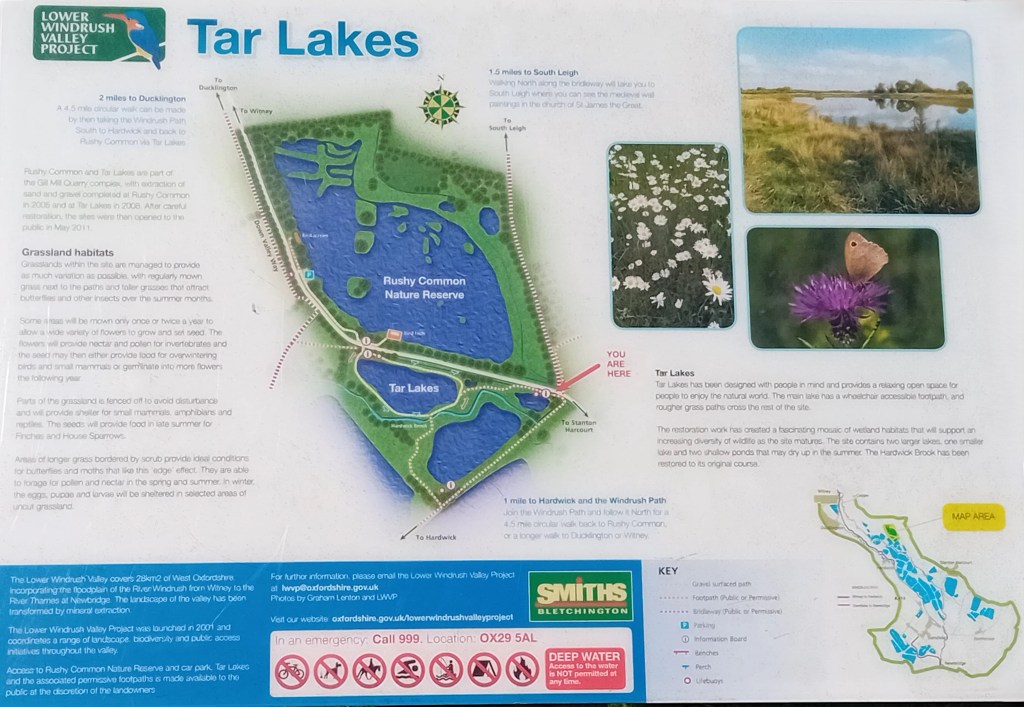

Not being one for nine-hour sea crossings, my itinerary was a brief evening BA flight from Heathrow, returning at Sunday lunch-time. After a night in a Schiphol airport hotel I collected my hire car early on Saturday morning, then it was a frosty 84km (52 mile) drive north to Den Helder where I took the 10:30 ferry. When I arrived on site (53.079906, 4.896607) a large number of cars were parked on the land side of Lancasterdijk, and upon reaching the crowd my quest was on view in the middle distance offshore.

For my first two connects I asked other birders to find the Spectacled Eider for me in my scope. But after that and with my eye in I relocated it for myself many times over the ensuing three hours, always with a degree of searching. Whenever I found it again the bird stood out from its companions, being noticeably smaller than Common Eider without that other’s elongated head and bill profile, and with it’s own distinctive head pattern. Everyone present was papping away but that did not mean they were getting good results in the morning mist and low sun. Fortunately I am once again indebted to the inestimable Richard (see here) for allowing me to illustrate this post with his own outstanding pictures from an earlier visit.

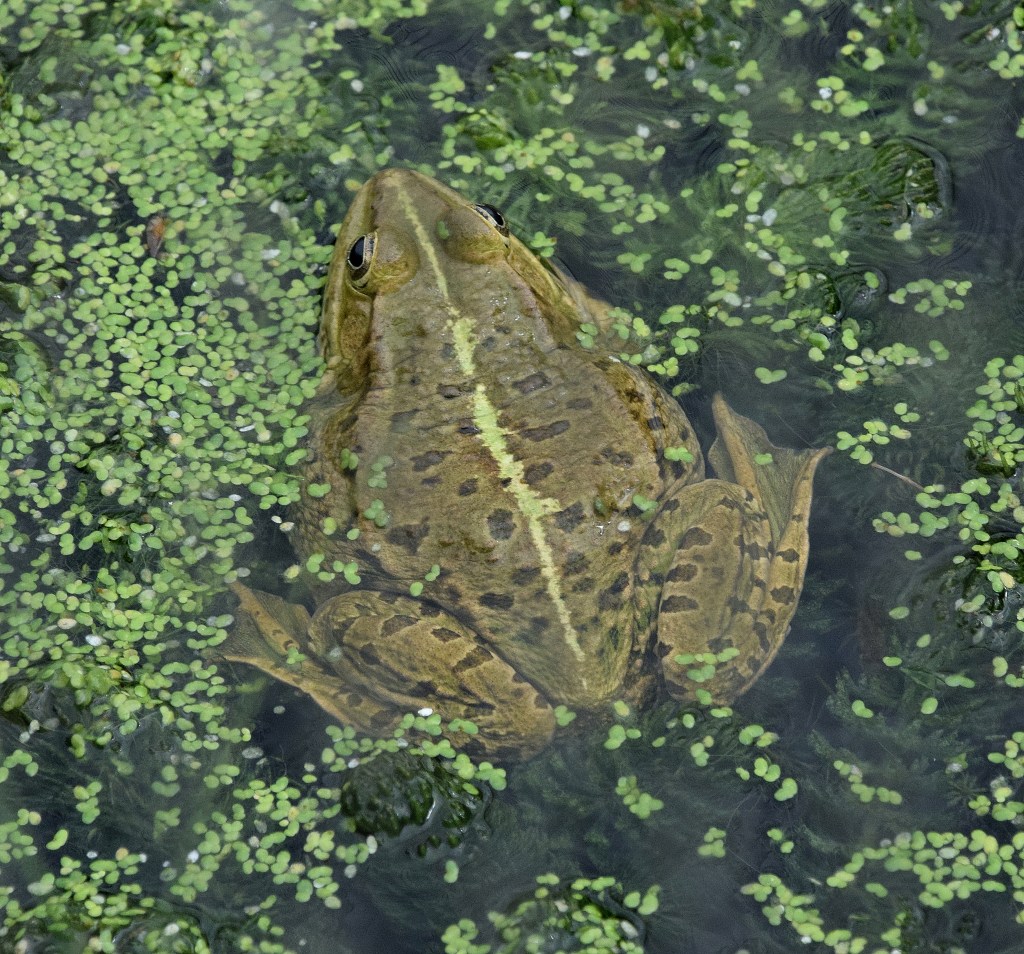

Common (left) and Spectacled Eider to separate at distance

To put things in perspective, the upper picture (above) is how things actually looked from shore, and that was with my own 300mm lens and a 2x converter. It would be a pity not to include my personal pictorial record of the occasion (above, right) if only to show I really was there. It cost an extra £80 to take my scope in a hold bag, padded out with warm winter clothing, and both were essential. The following image, an attempt to be creative, perhaps further conveys the difficulty of the viewing conditions, though in the afternoon the light was clearer. A constant stream of observers came and went throughout my time there.

Spectacled Eider (see here) breed on Alaskan and far eastern Russian coastal tundra, typically dabbling for food in shallow water. They move a little to the south to form large wintering rafts in gaps in the sea ice between the two continents, at which time they become quite deep underwater divers to 250 feet. The Alaskan population is estimated at between 3 & 4000 nesting pairs, while the Russian contingent is said to be much larger. It was not known exactly where they wintered until the 1990s, with the aid of satellite transmitters tracked by US Fish and Wildlife Service aircraft. With this gain, just the sixth and by far most southerly Western Palearctic record, I have now observed all four Eider species; the others being Common, King (see here) and Steller’s (here).

On Saturday night I stayed at the most excellent Hotel de Lindeboom in Den Burg (see here), 10 minutes from the ferry terminal. The food there was so good I thought the people of Texel must be encouraging “duck tourists” to visit again. The island is of course a world-renowned birding location, and I myself went there a previous time on a group tour in 1988.

My March 2024 run-in with El Montezuma in Spain had rather stemmed my motivation for solo wildlife travel since. But this just seemed too good to miss. If these things are out there within accessible range I will still get up and go for them. I was amongst the first British birders on Fuerteventura for the Dwarf Bittern in December 2017 (see here), one of few to take advantage of the November 2019 Pine Grosbeak irruption in Oslo (here); and now I have done this. I believe I am also just the second Oxon birder to have gone to Texel this time. Little is more fulfilling than these near-continental adventures.

I made a £630 outlay on this experience, but if you don’t buy the ticket you don’t see the show. Over seven days a first county Green-winged Teal, first national Lesser White-fronted Geese (BOU category 5), and now this ultimate European and WestPal list addition have provided a welcome spate of new and different birding. If records like those are available … Woof!!