Options for evolving through Orchids are diminishing now. At this stage of proceedings, as a year earlier my attention turned to the specific group of Orchidae known as Helleborines, of which three previously unobserved species were available to convert within sensible range. After recording two of those for the first time earlier in this week I at first concluded they are connoisseur items best left to hard core Orchid hunters and dedicated patch workers. But my eventual experience softened that stance when I self-found one of them at a BBOWT reserve.

The uncommon and unobtrusive Green-flowered Helleborine grows in Beech and other woodlands or coastal dunes, on calcareous and sandy soils. A cluster was reported on Facebook at BBOWT’s College Lake headquarters (HP23 5QG – SP935139 – see here) on 13th. On my visit there six days later it turned out that had been in a non-accessible area, but fortunately I engaged with a volunteer whose role is to show people around the reserve. He led me out to a likely spot and after some searching was the first to locate a specimen at the trackside. With our eyes now in, between us we then noticed three more plants that were all in pristine condition.

Green-flowered Helleborines at BBOWT College Lake

My research when reading up on this species a few days previously had suggested the flowers can appear to be almost permanently in bud, opening only partially to reveal a paler green lip sometimes flushed with pink. This cluster (pictured above) contradicted that since the flowers were all fully open. It was in fairly deep shade, so each plant was shorter with fewer blooms than is typical when GFH occurs in more open woodland. Having posted this on Facebook to seek confirmation of the ID, I was told by other group members there are various places on the reserve where this Helleborine might be found.

On my way to College Lake I stopped at BBOWT Aston Clinton Ragpits (SP888107) to re-visit the Broad-leaved Helleborines observed there last year at the woodland edge near the reserve entrance. It must be an intermittent species since only two were apparent this time, both in bud. But wandering at random into the Ragpits themselves I encountered some attractive var alba Pyramidal Orchid (below).

Pyramidal Orchids var alba at Aston Clinton Ragpits, Bucks

Things had got going on Monday 15th with another day trip to the Gloster Cotswolds, courtesy of Ewan whose local colleague Duncan had invited us to view two scarcities he had found at a site he surveys regularly. My research suggests Green-flowered Helleborine is variable in appearance and prone to appearing then vanishing at known sites, then re-occurring in unexpected nearby places. Numbers within usually small colonies may vary from year to year according to wetness, so this season must be a good one! The examples viewed on that day (pictured below) were a more typical height of up to 40cm, with each stem carrying well-spaced leaves and up to 20 closely clustered and barely open flowers.

The enigma that is Green-flowered Helleborine at the Glos site, and Narrow-lipped (far right)

Trickier still and greatly declining across its highly localised national range, Narrow-lipped Helleborine is a short-lived and self-pollinating deep shade lover that cannot tolerate direct sunlight. It blooms for around 10 days only in July and August, being particularly associated with Beech trees on calcareous substrates. The skinniest of the three Orchids viewed today, it may reach 70 cm or more in height. The drooping, well-spaced and very open flowers are yellow to olive-green in tone with no trace of the closely related Broad-leaved’s violet or purple hues. That is if such detail can be made out then captured in the preferred gloom such as we encountered them in.

Our guide told us they occur at more Cotswold sites he surveys, but the two at this spot were his only finds this season. Others in the vicinity had fallen foul of mammal browsing. The survivor (pictured above, far right) is what I would describe as challenging. Proper photography must require artificial lighting to capture such a subject adequately. The record shot is the best I could gain in the circumstances, using my phone. See here for an apt pictorial appreciation of the conundrum concerned.

Having learned all these complexities in writing up this post, the reaction was to opt out of my original July plan of seeking such quests locally at historic locations. Since both the easily overlooked plants are vulnerable to disturbance and particularly trampling, by agreement with our inestimable host who had self-found them I cannot reveal their precise locations herein. I will admit to not being swept off my feet by either of the rather unsubstantial-looking pair, but they are scarce and difficult to find Orchidae that I had not seen previously, so their rarity value must carry the day.

At the start point of our walk were far more plentiful Broad-leaved Helleborine (pictured below) of an atypical deep red-flowered form. They were rather more the ticket for me visually and still in a quite early stage of blooming. It was only my second record of another erratic and declining species, including this tonal variant, that I had observed a year ago at Aston Clinton Ragpits (see here).

Broad-leaved Helleborines

I next considered going for Dune Helleborine, a similar and as short-lived, but taller species to Narrow-lipped that has occurred at a one-off inland location in Warks since 2017 (see here). But less than enthusiastic advice from a top level contact of Adam suggested it might not be worth doing as the site has become poorly managed so the fragile colony is barely clinging on. Just four stems there had been in bloom for over a week with no mention in our Facebook group, so maybe others agree. This post’s comment certainly does.

With these successes it remained to check Oxford’s own fens for Marsh Fragrant Orchid, following on from my recent first experience of them in Hants (see here). The first to be reported from BBOWT Dry Sandford Pit (OX13 6JW – SU467997) for three years had been posted on Facebook and Ian tracked it down over the previous weekend (pictured below, left). Then Ewan visited on 18th and located a whopping 30-plus plants in another part of the fen, more than Wayne could ever remember at the site.

Marsh Fragrant Orchids at Dry Sandford Pit, Oxon

I therefore met Ewan there on Friday morning (19th). He led me along a newly trodden way through the fen and before us were indeed a large quantity of MFO, whose fragrance filled the air all around. I have been to the reserve many times over the years but had never dared to venture into this part of the seriously off-piste habitat. Now others had done so ahead of us as the way through was clear. So perhaps this significant cluster has gone unseen over the aforementioned three year interval, during which BBOWT had in any case blocked access to the fen … who knows?

This post’s new records bring the total of Orchids I have observed in the British Isles to 39, including three notable hybrids. Early Spider Orchid next spring, that I was too slow off the mark to convert this season, could round that up to a suitable stopping point perhaps. But these highly motivational wild plants neither only come out when the sun shines nor fly away just before I get there, so who knows?

Herewith my national Orchid list to date (in running order per my Blamey, Fitter & Fitter Domino wild flower guide, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2nd edition 2013)

- Common Spotted Orchid – widespread

- Heath Spotted Orchid – Loch Eil, Allt Mhuic reserve, Woodsides Meadows

- Early Marsh Orchid – Lye Valley, Parsonage Moor

- Southern Marsh Orchid – widespread

- Northern Marsh Orchid – Glenroy, Fort William

- Chalk Fragrant Orchid – widespread

- Marsh Fragrant Orchid – Mapledurwell and Greywell Fens, Dry Sandford Pit

- Heath Fragrant Orchid – Allt Mhuic reserve

- Pyramidal Orchid – widespread

- Early Purple Orchid – widespread

- Green-winged Orchid – widespread

- Musk Orchid – Grangelands (gone over), Noar Hill

- Small White Orchid – Allt Mhuic reserve

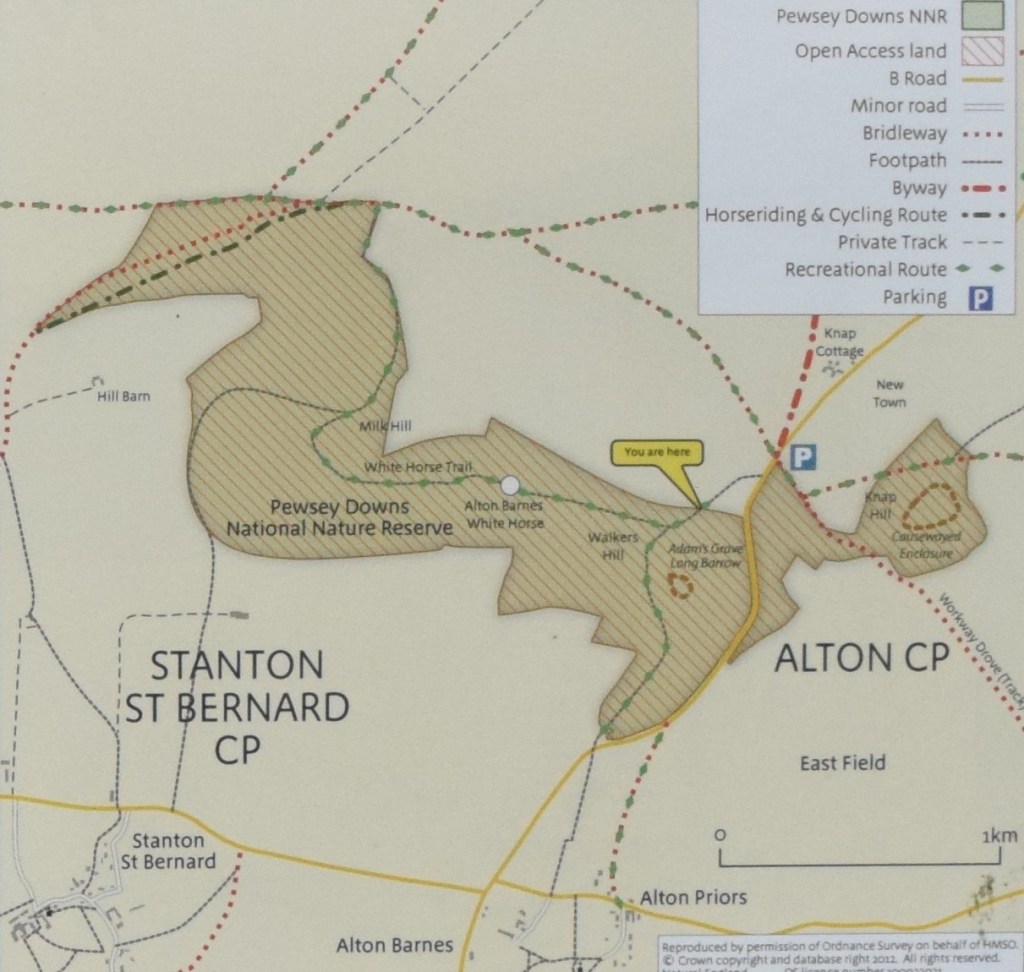

- Burnt Orchid – Clattinger Farm, Knocking Hoe, Pewsey Downs

- Lady Orchid – Hartslock reserve

- Lady X Monkey Orchid – Hartslock reserve

- Military Orchid – Homefield Wood

- Monkey Orchid – Hartslock reserve

- Man Orchid – Barnack Hills & Holes, Swaddywell Pit

- Lizard Orchid – Oxon site, Berrow Dunes, Sandwich Bay

- Common Twayblade – widespread

- Frog Orchid – Bald Hill, Morgan’s Hill

- Frog X Common Spotted Orchid – Morgan’s Hill

- Greater Butterfly Orchid – widespread

- Lesser Butterfly Orchid – Allt Mhuic reserve, Pewsey Downs

- Bee Orchid – widespread

- Fly Orchid – Homefield Wood, Warburg reserve, Cotswold site

- Fly-Bee hybrid Orchid – Cotswold site

- Autumn Lady’s Tresses – Greenham Common

- Marsh Helleborine – Dry Sandford Pit, Lye Valley, Mapledurwell and Greywell Fens

- Violet Helleborine – Warburg reserve

- Broad-leaved Helleborine – Aston Clinton Ragpits, Cotswold site

- Narrow-lipped Helleborine – Cotswold site

- Green flowered Helleborine – Cotswold site, College Lake

- White Helleborine – Homefield Wood, Grangelands, Aston Clinton Ragpits

- Narrow- or Sword-leaved Helleborine – Rodborough, Chappett’s Copse

- Red Helleborine – Windsor Hill, Bucks

- Bird’s Nest Orchid – Warburg reserve, Pulpit Hill, Colesbourne

- Giant Orchid – South Oxon

What remains is either difficult or beyond the distance I would consider travelling to connect with rare birds. I would struggle for instance to raise enthusiasm about miniscule mire dwellers such as Bog, Fen or the much lauded Coral Root Orchids. Likewise Lesser Twayblade or Creeping Lady’s Tresses, purely because they are residual species on a required list. This has been a wonderfully diverting project over the past two summers, but I am missing new and different butterflies to record dreadfully. Whither next?