Others have trod this path before me. When the better stuff seems like too much trouble but every so often I go out and add a few anyway to an at best half-hearted year list, it is possibly time (county ticks such as Black-winged Stilt aside) to give annual Oxon birding a rest. Likewise I have felt little inclination to re-work the English insect portfolios yet again this year. So as an alternative new season pursuit I have elected to seek out up to 30 of the 53 native British Orchids that can be found in my home county and neighbouring Bucks. The earliest occurring species can all be found at sites close to home, so that is where I started. Those covered in this post (in order of observation) are:

- Early Purple Orchid @ Sydlings Copse

- Green-winged Orchid @ Bernwood Meadows, Asham and Wendlebury Meads

- Heath Spotted Orchid @ Woodside Meadows

- Early Marsh Orchid @ Lye Valley and Parsonage Moor

Sydlings Copse, OX3 9TY – SP 559096

BBOWT reserve (see here) to the north-east of Oxford and just south of RSPB Otmoor, accessed on foot (600 metres) from a small lay-by on the B4027 road or by bridleway from Barton.

An unusual mix of habitats at this very diverse and fascinating site comprises ancient broad-leaved woodland, limestone grassland, reed bed, fen and rare Oxfordshire heathland; that between them support more than 400 plant species. After an earlier reconnoitre I visited here on 11th May to view Early Purple Orchid. Taking the right hand fork from the reserve entrance I found 50-something plants, mostly characterised by tall, slim flower spikes in shades of purple, through a gate at the end of that track.

This is the third most widespread British species and as the name suggests is an annual vanguard. Generally common, it may be found growing amongst Bluebells, Cowslips and Wood Anemones in coppiced woodland; as well as on rough pasture, open downland, meadows, roadsides and railway embankments. Each open and irregular-shaped bloom has 10 – 50 flowers that emit a strong smell of urine to attract pollinators but do not produce nectar.

Early Purple Orchids

Bernwood Meadows HP18 9UR – SP 606111

BBOWT reserve (see here) on the border between the two counties, north of Stanton St John and east of Horton-cum-Studley, with a small parking area (max four spaces).

There are three traditional hay meadows here that are managed to support over100 different wild plants, and host England’s largest and most well-known profusion of Green-winged Orchid. Having sought out earliest specimens through April (see here) to familiarise myself with the species, I came back on 11th May to take in the full, many-thousand strong spectacle of peak season (pictured below) that did not disappoint.

This “petite” (5 – 15 cm) Orchid of unimproved grasslands was once commonplace but its range has halved with agricultural intensification. It is now one of the most rapidly declining British species away from sympathetically managed habitat where it tends to grow in large colonies, such as here. The name comes from green or bronze parallel veins in the hood of up to 25 helmet-shaped flowers that grow in a loose, linear bunch at the top of the single stalk. The inflorescence may be of various shades, mainly purple but ranging from pale pink, through mauve to white. On this visit I concentrated on pictorial records of the less frequent colour forms (pictured below).

Green-winged Orchids

Asham Meads, OX5 2RF – SP 590143

BBOWT reserve (see here) accessed by bridleways from a minor road between Murcott and Boarstall (with unfriendly signage), or from Horton-cum-Studley (welly boots essential).

Three damp meadows here support scarce communities of marsh-loving plants including huge numbers of Green-winged Orchid in spring. I visited on 16th May, choosing the less hostile southern route in, and though spotted twice by resident farmers was not seen off. Getting there through wet, muddy ground was something of a challenge though after recent prolonged foul weather, but what eventually awaited me was well worth the effort. It was indeed a second spectacle to rival Bernwood Meadows (pictured below), and the site’s remoteness added a certain extra evocative quality and atmosphere to proceedings.

It is impossible to move around Asham Meads without trampling habitat so I limited myself to the near end of the Lower Marsh, luxuriating in a sense of peaceful solitude all the while. These (below) are a few of the plants that caught my eye on this occasion.

Green-winged Orchids

Woodsides Meadow, OX25 2PT – SP 556177

BBOWT reserve (see here) accessed by bridleway from a minor road south-west of Wendlebury.

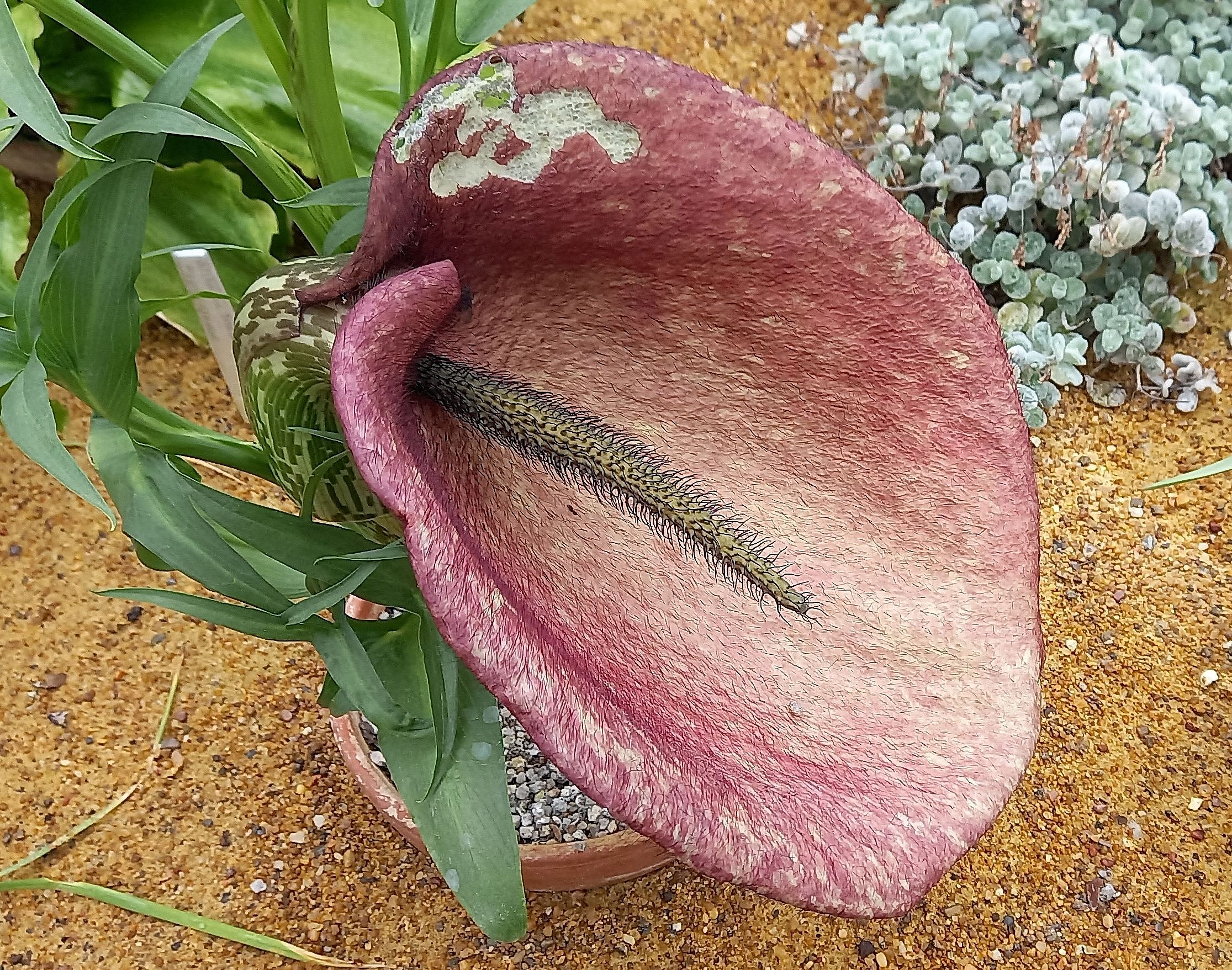

This three-field site is managed as traditional hay meadows characterised by medieval “ridge and furrow” plough marks. It is part of the SSSI-classed Wendlebury Meads complex of remnant calcareous pasture, and supports more than 100 different wild plants. I moved on from Asham Meads to what is a further secluded gem on 16th May. Having read that Green-winged Orchid occurs here too, in scanning for those tall, slim forms I at first failed to notice the large numbers of young and far more petite, site-speciality Heath Spotted Orchid that were looking straight back at me. But once I got my eye in I kept on finding more and more of the latter, which I had observed just once before in Scotland last year.

This is as far as I know the only Oxon location for this Orchid, that is also found at four heathland sites in neighbouring Berks. My research reveals the species occurs extensively on acidic soils across most of its range but will also colonise calcareous pasture where it still survives, such as here. To my unpractised eye today’s plants all had a “miniature” and less robust quality than the closely related Common Spotted Orchid that is more typical of non-acidic habitat. I initially took that as the diagnostic rather than subtleties in the blooms.

Heath Spotted Orchids

Reading into the latter, I found the description (see here) of HSO flowers as “being washed with a pale pink and having many purple marks and discontinuous lines upon them that do not form the well defined loops of CSO”, to be the clearest indicator. The above sequence I believe clearly shows this, but I am not so sure about the outer plants below that my Seek app also identified as HSO but possibly look more like the bolder CSO. As always I am open to informed guidance here.

There is clearly a lot of variation in flowers of both species. Most sources agree that the faintly scented HSO spikes are shorter than CSO, usually between 10 and 20cm high, and tend to be conical. In the south of England HSO is said to bloom two weeks earlier, and vice-versa in the north continuing through July. To complicate matters, the two species readily hybridise, as HSO does with other marsh orchids. The “spotted” in the names refers to spots on the leaves rather than on the flowers themselves.

I came back here two days later on 18th finding many more plants (pictured below) erupting in clusters from the damp plough and furrows, and having read up on all this earlier in the morning became convinced that what I was finding was indeed HSO in a rather special location. After checking things out with trusted sources HSO’s historical presence was confirmed, though possibly not too many people visit here for the purpose. In my first serious Orchid season I feel very glad to have done so

Heath Spotted Orchids

Wendlebury Meads, Oxon – SP 563173

An area of traditional calcareous pastures, accessed on foot to the north-east of Charlton-on-Otmoor, lying on private land but crossed by a public right of way that there is nothing to stop anyone wandering from.

Visiting on 18th May, the first meadow I reached contained a third Green-winged Orchid spectacle (pictured below) to rival Bernwood Meadows and Asham Meads. Once again the soothing sense of solitude here appealed to my non-preferred option of doing these things alone, and I rejoiced in the awareness that such out of the way places still exist in our frenetic world, not to mention so close to home. These fields, still showing evidence of medieval ridge and furrow ploughing, for whatever reason have never been “improved” or farmed by modern methods. Such calcareous pasture was commonplace in southern England up to the early 20th century but very little now survives, so today’s location offers an appealing experience of ecosystems from largely lost times gone by.

After that first field the path continued across three more in which any Orchid interest if present was well hidden, until I reached the hard access track to Woodsides Meadow that I re-visited. The onward route eventually skirted a further part of this intriguing complex known as Mansmoor Closes, a series of enclosures on private land with no access that are managed in the same way, though some were being grazed by cattle or horses. More large concentrations of what must have been GWO were visible in the middle distance from the private concrete road along which the bridleway back to Charlton-on-Otmoor ran.

This morning was another thoroughly stimulating and spirit-cleansing diversion, such as this entire exercise is so effectively offering, and I am only up to three Orchids so far. It’s difficult to imagine for instance how many hundreds of GWO I must have scrutinised for most attractive items. Just being in the “lost places” they still thrive in has been more rewarding than I could have imagined. Much more will be added to this from here on in.

Lye Valley, Oxford OX3 7HP – SP547058

A local nature reserve (see here) administered by Oxford City Council in partnership with BBOWT and volunteer groups, accessed on foot from surrounding residential streets.

In the fourth week of May my attention turned to Marsh Orchids, Early and Southern of which as the name suggests the former goes first. Oxford and its environs has two remnant areas of nationally rare calcareous fen habitat that support both items. On the morning of 22nd I visited one of those that is close to my favoured supermarket. It didn’t take long to find what I was looking for, there being in excess of 50 Early Marsh Orchid in full bloom in one portion of the valley.

This species was found historically in wet grassland areas including marshes, floodplains and wet meadows such as Iffley and Bernwood; but is now lost from around 40 per cent of it’s former range due to land drainage and (like GWO) modern agricultural practice. Where it survives EMO is said to occur mainly in small numbers so this must be a good site. The flowering period is from late May to early July.

Having thus gained a personal first sighting I was expecting the flower size to be larger. As with plumage topography in birds, I do not intend to go into petals, sepals, lips and hoods too much herein; being content to let my pictures distinguish the plants presented. EMO in Oxon and Bucks are all of the same sub-species, and there are four more with interesting colour variation in different parts of Great Britain. Hybridisation with Southern Marsh, Common and Heath Spotted is also a factor, producing many intermediate forms.

Early Marsh Orchids

The final picture in the sequence above was taken later on the same day at BBOWT Parsonage Moor (SU461997), part of the Cothill Fen complex to the west of the city. This has been the classic Oxon Marsh Orchid site over the years but my understanding is they occur there only in small numbers. On this occasion I located just two specimens, so Lye Valley not for the first time in recent memory provided the superior experience.