What a difference a new and different bird to go after and see makes! Little could have been more welcome than overnight news that an Oxon mega had been discovered at the prime stomping ground that is Farmoor Reservoir.

My home county is enjoying a purple patch at present where Nearctic ducks are concerned, with the American Wigeon (see previous post) and now this latest item joining three over-wintering Ring-necked Ducks in different locations. The latest alert went out just before 4pm yesterday but seemed lukewarm and uncertain, being cited as “possible” then “putative” before nightfall. So recalling a Lesser Scaup candidate at Farmoor in November 2017 that was overruled as a hybrid, I opted to wait for the ID to be confirmed this time. On rising today that decision had been made and with it came a familiar but recently all too unavailable sense of purpose.

When I reached site just after 8am some earlier arrivals had already relocated the bird but it had flown and they were walking back along the causeway. I followed some of them to where it had been seen to land but there was no sign and alarm bells rang in my head. The group was about to walk on clockwise around F2 when I received a call saying our quest was now in the other direction in front of the sailing club, and so I briefly became a man of the moment for passing on that news. And when everyone present regrouped my second career Lesser Scaup stood out at once amongst a small group of Tufted Duck (below).

My only previous sighting of this species was at Cardiff Bay, Glamorgan in February 2015 (see here). It is common and widespread across North America and a regular vagrant to the British Isles with up to 15 records in some years. There have been two of them in England recently and since one of those, a drake at Staines Reservoir, Surrey has not been seen there in the last two days it is assumed that individual and today’s are one and the same. Similarly the still present American Wigeon is now thought to have commuted between Shapwick Heath in Somerset and Oxfordshire before settling at Otmoor.

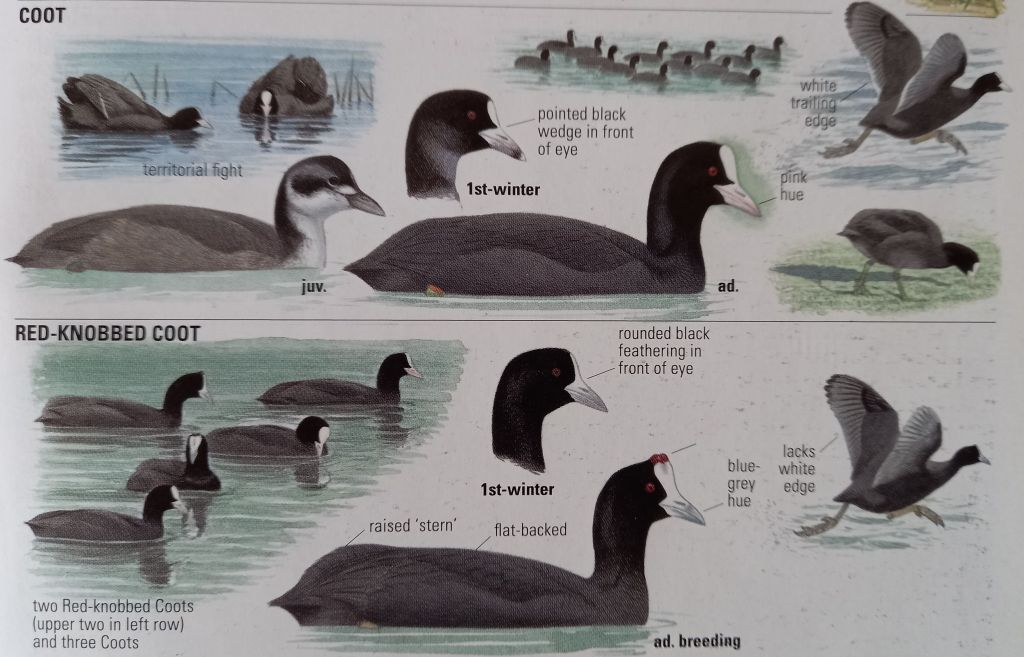

Lesser Scaup is as the name suggests a noticeably smaller and more slightly built duck than either greater Scaup or Tufted Duck. Two of the most obvious diagnostics compared to greater in drakes are the high-crowned, less rounded head shape and a coarser vermiculation on the upper parts darkening to the rear. The latter feature was very apparent in today’s bird that I viewed at much closer range than previously in Cardiff Bay. The head shape can vary in appearance as the peaked crown is not a factor of skull structure but arises from elongated feathering, possibly a “bad hair day” as the Oxon birding colleague alongside me put it. This can lead to contentious IDs where the Nearctic duck is concerned, but not today.

Once the Farmoor bird (more muddy record shots above) was pinpointed in front of the sailing club it proceeded to drift up and down the northern edge of F2 fairly close in to the causeway with its Tufted companions, diving all the while. As several other birders commented, this was unusual in a site scarcity which more usually choose to favour the furthest corners of the twin reservoirs from the entry point. Once news went out again more of Oxon’s finest came and went over the ensuing three hours that I remained on site.

I learned the previous Lesser Scaup here had been in March 2000, though there was another elsewhere in the county in December 2007. So high (260+) county listers would presumably have it but many of those from the high 250s downwards could be expected to visit. This was a proper old school county twitch, the first in a while and at least while I was there surprisingly free of social media driven peripheral observers.

A female greater Scaup, always a good bird to see has also over-wintered here, which I took the opportunity to catch up with today. Sooner or later Farmoor Reservoir like any large inland water body will always deliver anew and the Lesser Scaup is actually my 250th Oxon county bird, including two heard only and six non-BOU recognised species that still count for me. More widely my four county birding events so far in 2023 of an early January Yellow-browed Warbler in central Oxford, a new Starling roost in Eynsham, and the two Nearctic ducks have all been motivating. I will of course, with whatever assistance the birding gods might provide, persist in encouraging my recent mind set to shift.