Southern Turkey: 16 – 20 June 2019

Lifers do not come any huger than Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin (pictured below). This long sought bird was my top pick amongst 21 WestPal list additions gained on the five-day 2019 Birdwatch Magazine / Wildwings tour of southern Turkey.

Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin

The others, in order of appearance were: Brown Fish Owl, Graceful Prinia, Eastern Bonelli’s Warbler, Krüper’s Nuthatch, Cretzschmar’s Bunting, Bimaculated Lark, Upcher’s Warbler, White-throated Robin, Asian Crimson-winged Finch, Pale Rock Sparrow, White-winged Snow Finch, Moustached Warbler, White-headed Duck, Caspian Snowcock, Red-fronted Serin, Radde’s Accentor, Finsch’s Wheatear, Syrian Woodpecker, White-throated Kingfisher and White-spectacled Bulbul.

This tour was devised and is led by the Turkish bird authority Soner Bekir, who with two colleagues trades as Birdwatch Turkey. There are not many birders in the country and this dedicated group of enthusiasts are between them responsible for maintaining national records and guiding foreign visitors. Birding tour company groups and smaller private parties are both catered for.

The tour group (from left): Stuart Greer, Ian Moig, Andy Davis, Soner Bekir (leader), Tom Hanson, Gordon Cox, Andrew Emmerson, Andy Middleton (hidden), John Hanson, Peter Reay

Much of the bird life described herein was observed fleetingly or distantly, but I have included some images I was able to gain. These make no pretence of being “photographs” but convey how the birds were actually experienced within the constraints of available time and the limitations of my equipment. My thanks to tour colleague Andrew Emmerson for providing more pictures of other birds that we observed.

Day one (16th): Oymapinar Lake (a) – Manavgat beaches (b) – drive to Akseki (c), Cimi village (d) and valley beyond (e)

a – Brown Fish Owl (1), Western Rock Nuthatch, Red-rumped Swallow

b – Graceful Prinia (2), Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin (3)

c – Eastern Bonelli’s Warbler (4), Eastern Olivaceous Warbler, Collared Pratincole, Krüper’s Nuthatch (5 – lunch stop)

d – Olive Tree Warbler, Middle Spotted Woodpecker, Sombre Tit

e – Black-eared Wheatear, Woodchat Shrike, Masked Shrike, Rüppell’s Warbler, Black-headed Bunting, Ortolan Bunting, Cretzschmar’s Bunting (6), Eastern Orphean Warbler

– lifers are denoted in bold type –

==============================

After flying in to Antalya late on the previous afternoon we stayed overnight at the town of Manavgat around 40 km to the east. The tour opened with a first-light start at Oymapinar Lake, to the north on the River Manavgat. Here there is a large water body behind a hydro-electric dam (pictured below) that is described as the only realistic site west of India where Brown Fish Owl may be encountered.

Oymapinar Lake © rights of owner reserved

Our extremely rare and localised target was re-discovered in southern Turkey from 2009 (see here). For many years this enigma was thought to be extinct in the Western Palearctic. There had been historic records from Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Syria, and Turkey that indicated a larger presence, but no firm sightings until two breeding pairs were confirmed at today’s location. Since then visiting birders and our guide’s own team have tracked down breeding BFO at several more sites, but Oymapinar remains the only readily accessible one. These Owls are active by night and roost on cliffs through the day. We were taken out to see them by boat, long before Turkish general public arrives at what is also a popular recreational attraction.

The first individual seen was a juvenile (above, centre) that stood out readily on it’s exposed perch in a canyon at the eastern corner of the lake. Then the parent birds (above, left and right; and below, left) were located in deeper shade on the opposite shore. These are largish (L 50 – 58cm, WS 1.25 – 1.40 m), broad-headed Owls with horizontal ear tufts. The strong protruding bill completes a characteristic profile. Flight feathers are brown with darker barring and the tail is strongly barred brown (per Collins).

We then moved on to the big canyon at the lake’s northern end. The historic breeding pair there relocated elsewhere in 2018, but one of that year’s fledglings remains on site. This individual provided my visit’s best pictures (above, right and below, left). On the drive back down after leaving the lake, Western Rock Nuthatch (below, right) and Red-rumped Swallow were both active below the dam itself. This was my fourth record of the former after others in Greece in 2017 and 2018. It was seen a number of times during this trip, while the latter were regular. There is also a local company that takes visitors to Oymapinar Lake (see here).

After breakfast back at our hotel we drove east from Manavgat along the coast in search of Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin and Graceful Prinia. I was at once impressed by how quickly these birds were located, a scenario that repeated itself time and again throughout the tour. Soner is a superb guide. He had locations to which we were taken for each trip target, one after another and they were mostly found within minutes.

The first-named bird’s importance to me as a lifer derives from being a much sought species amongst birders visiting southern Portugal, that had eluded me during my solo trip there in May 2014. Then I concentrated my butterfly and dragonfly searches on areas where RTSR might also occur, but without success (scroll down this page for the trip report).

Also known as Rufous Bush Chat, with various derivations of the two names, this is a summer visitor across north Africa and the Middle East, as well as the southern Iberian and Balkan peninsulas; wintering south of the Sahara. There are two races, with birds in Turkey and Greece differing subtly from those occurring elsewhere. This is a bird of skulking habits that favours dry, open habitats. It may be found flitting amongst dense shrubbery but also more openly on trees, the tops of bushes and posts.

When seen on the ground RTSR hops about, flaring and bobbing its long tail that is often held in cocked and spread profiles. When perched the bird also displays the tail in these ways and also may droop the wings before giving them a little flick forward. It feeds mainly on the ground taking insects, their larvae and worms; turning over the leaf litter to find such prey.

Now, one individual, doing most of those things as it moved around, gave itself up to my camera quite nicely (pictured above). These images are all the more satisfying for having been captured during a full-blown allergy attack that unusually abated after I stuffed serviettes up my nose then slept during the drive to our next location. But the affliction is not so easily suppressed and I eventually paid for attempting to do so as things played out their course right through my first weekend back home.

Graceful Prinia was no so co-operative, being observed rather more distantly, but the profile (pictured above) was unmistakable. This small, active, variable grey-buff warbler is a resident breeder in north-east Africa and southern central Asia, of which one sub-species extends into this coastal region of Turkey. It nests low down in tall grass and dense shrubby habitats, often along ditches, water courses or pools such as at this site. The wings are short and rounded and the long tail is often cocked or sometimes held in a fanned position.

After these successes we drove on north-eastward through the Taurus Mountain range towards the town of Akseki that would be our overnight stay. During stops en route both Eastern Bonelli’s and Eastern Olivaceous Warbler were encountered. The first of those was a welcome lifer as it meant I have now seen both species of Bonelli’s, the western variant having been recorded in les Cévennes, France in May 2016. Collared Pratincole was also observed during this relocation.

Krüper’s Nuthatch © and courtesy of Andrew Emmerson

Upon reaching our destination we headed up into the hills and made a lunch stop at a small burial ground in a wooded area. Here a Krüper’s Nuthatch (pictured above) was located, the tour’s only sighting. This coniferous forest dweller is sometimes described as being near endemic to Turkey, though there are lesser numbers in Georgia and Russia, and also a small breeding population on the Greek island of Lesvos (see here). Krüper’s is smaller and quieter than Eurasian and Rock Nuthatches with a distinctive head pattern, and rusty brown breast patch and under tail feathers.

We next moved on to a village called Cimi, where stopping the minibus our guide declared: “The target here is Olive-tree Warbler.” After walking no more than 50 metres he pointed to one side, saying: “Olive-tree Warbler calling over there,” and thus things continued throughout the tour. But this species, which I had recorded before in Cyprus and Greece, is seldom easy to see well. OTW (above left) was encountered a number of times subsequently but I only caught glimpses as these hyperactive birds moved around. Sombre Tit (above right) was similarly difficult at Cimi, though I did get a recognisable picture of Middle Spotted Woodpecker.

Middle Spotted Woodpecker

A rain break then ensued, and this was the weather pattern throughout the tour. Each day there was a thundery build up before heavy showers at unpredictable times. But the interruptions didn’t last for long and we lost no sightings to inclement conditions. Soner’s strategy this time was to drive on and sit out the rain, then enjoy the re-emergent bird life once the sun came out again. That was exactly how things transpired. Around an hour parked in a scenic upland valley gave way to a very pleasant evening session during which I appreciated just how different the birdscape is in the region.

Rüppell’s Warbler © and courtesy of Andrew Emmerson

It helps of course to be travelling with an expert who knows exactly where to find all the best birds. First we watched a pair of Rüppell’s Warbler (above) feeding young, only my second ever record after one on Paphos headland, Cyprus in April 2012. Then a Black-eared Wheatear put in an appearance. Woodchat and Masked Shrike were both active, along with Ortolan and Black-headed Bunting (pictured below, left). All these species except for the Rüppell’s were seen fairly regularly through the tour, especially the last-named.

The prime targets at this site were Cretzschmar’s Bunting (pictured above, right) and Eastern Orphean Warbler. To attract the former our guide played a recording as we walked along and after maybe 20 minutes a pair duly flew in. This is another very important lifer being a regional Bunting that is absent from my Cyprus list. CB is a summer visitor to Greece and Turkey, southward to the Red Sea, beyond which it winters. Now I can even spell the name without thinking too much though that still might be difficult after a few beers.

Distant Eastern Orphean Warbler (record shot)

With this record duly gained the next target was Eastern Orphean Warbler, that when located was another second ever for me after one in Greece in May 2017. The smudge amidst the yellowish vegetation in the above image indeed is one. Now a very long day’s agenda had been completed with aplomb, and I was set to sleep well whilst still being ready for a 5:30 am start in the morning. Naturetrek this tour was not!

Day two (17th): Overnight in Akski (a), Cimi village and valley beyond (b – pre breakfast), through low lying area to Sugla Lake (c), Bozkir (d – lunch stop), drive through steppe landscape to Karaman then via Lark sites to Eregli (e – overnight)

a – Laughing Dove, OTW and EB and EO Warblers again

b – Middle Spotted Woodpecker, Red-backed Shrike + Woodchat & Masked, Woodlark, Nightingale, Ortolan and BH Bunting

c – Black and White Stork, Black-crowned Night Heron, Purple Heron, Egyptian Vulture, Lesser Spotted Eagle, Booted Eagle, Steppe Buzzard, Long-legged Buzzard, Great Reed Warbler, Spanish Sparrow

d – Isabelline and Black-throated Wheatear

e – European Roller , Greater Short-toed Lark, Bimaculated Lark (7), Calandra Lark

==============================

Before breakfast we visited Cimi and the valley beyond that village again, seeing mostly the same birds again. The Olive Tree Warblers that interested our guide were again elusive, and Eastern Bonellis and Olivaceous Warblers were encountered as fleetingly. A Red-Backed Shrike showed itself amongst Woodchat and Masked cousins, while the song of Nightingale and Woodlark was carried on the air.

Landscape to the north-east of Akseki

The tour then moved on to the north-east, leaving the Taurus Mountains behind. We had been primed to look out for Laughing Dove in Akseki and one was spotted as we left the town. Our route next crossed low lying agricultural land (pictured above) towards the wetland site of Lake Sugla. We made several stops along the way, scanning for passerines and raptors. Booted and Lesser Spotted Eagle (below, left) were both noted along with a first Egyptian Vulture, Steppe and Long-legged Buzzard (below, right).

Long-legged is the default Buzzard in much of Turkey and occurred regularly through the remainder of the tour. This is a raptor that had been pointed out to me either briefly or distantly in the past, so I was pleased to gain a full understanding of how to identify it (see here) through some closer encounters now. Steppe Buzzard, the regional sub-species of Common Buzzard was also noted a number of times.

In one village where we stopped to check out the hirundines and Swifts, a White Stork nest (pictured below) also hosted many Spanish Sparrow as they commonly do. Somewhere in the landscape pictured higher above a Black Stork was foraging. Drainage ditches along our route and Lake Sugla itself held Purple and Black-crowned Night Heron, and Great Reed Warbler. All this was a very different birdscape indeed!

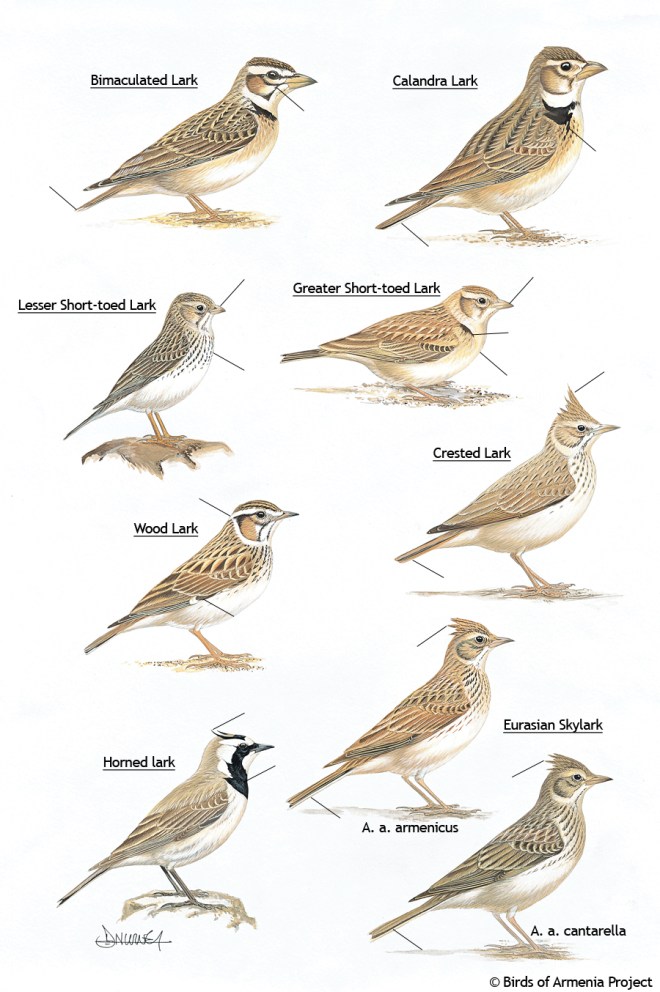

In the afternoon we drove on eastward through steppe landscape, to seek out more birds of that habitat. The main trip targets here were Larks, of which Bimaculated, Greater Short-toed and Calandra Lark were all located. The second of those was a bird I had recorded just once before in Portugal, but a respondent to that trip report queried my ID so it was pleasing to confirm its place on my life list here. Calandra is a Lark I have previously found difficult to pinpoint whilst knowing they are out there somewhere, while Bimaculated was entirely new. All three were seen well now. At one Lark stop we also came across the tour’s first White-throated Robin, but more of that lifer later.

Bimaculated Lark is similar in appearance to Calandra but around 10% smaller and relatively longer winged. It occurs from west-central Turkey through the Middle East and Central Asia. Calandra has a more western distribution but is also resident across parts of the migratory Bimaculated’s range. Both species are largish, robust Larks with thick bills, broad wings and short tails. Greater Short-toed is a summer visitor throughout the Mediterranean region and eastward into the Caucasus and Middle East.

Bimaculated Lark is similar in appearance to Calandra but around 10% smaller and relatively longer winged. It occurs from west-central Turkey through the Middle East and Central Asia. Calandra has a more western distribution but is also resident across parts of the migratory Bimaculated’s range. Both species are largish, robust Larks with thick bills, broad wings and short tails. Greater Short-toed is a summer visitor throughout the Mediterranean region and eastward into the Caucasus and Middle East.

Further notables during this leg of the tour were a pair of European Roller on roadside telegraph wires, Black-throated and Isabelline Wheatear (pictured above, right). The latter was observed a number of times again over the next two days. After a lot of driving through this day it didn’t rain until the evening. Our overnight stay was in the town of Eregli.

Day three (18th): Aladaglar mountains (a), Sultan Marshes (b)

a – Upcher’s Warbler (8), Barred Warbler, Isabelline Wheatear, White-throated Robin (9), Asian Crimson-winged Finch (10), Pale Rock Sparrow (11), White-winged Snowfinch (12), White-throated Robin, Black Redstart, Egyptian Vulture, Red-billed Chough

b – Long-eared Owl, Moustached Warbler (13), Great Reed Warbler, White-headed Duck (14), Bearded Tit, Ruddy Shelduck, Squacco Heron, Purple Heron, Glossy Ibis flying, Little Bittern, BCN Heron, Little Egret, Spur-winged Plover

==============================

From Eregli we drove north-east to visit Sultan Marshes National Park, a major wetland site. But the weather was looking threatening so to beat the rain we headed up into the Aladaglar Mountains to convert some montane passerine trip targets. There would be no shelter up there whereas the first location had hides and an on-site restaurant. Between them these two sites yielded an impressive seven life list additions.

Our first stop in these mountains was for Upcher’s Warbler (pictured above) that was soon located. This is a medium-sized, rather plain and drab looking Hippolais that breeds from Turkey south and east to Pakistan, wintering in eastern Africa. So we were observing the species right at the western end of it’s range, where it frequents scrubby areas especially favouring Tamarisk thickets. The supporting cast here comprised Barred Warbler, Isabelline Wheatear (below, left) and White-throated Robin.

The last-named (pictured below) was observed on the next two day’s as well, but were always fast moving and hyperactive so difficult to get pictures of. Male WTR are unmistakable and very attractive. During a nature break at this site a juvenile (above, right) dropped out of the next bush and so I was able to capture an image of sorts.

This is a summer visitor to south-eastern Turkey and countries to the south and east, wintering in East Africa; and so is another speciality of the area covered by this tour. Our guide recalled how in June 2011 his group were watching the bird when news broke of the famous individual in Hartlepool, north-east England at which some participants headed straight for the airport. Now that is hard core!

White-throated Robin ↑ and Asian Crimson-winged Finch ↓ © and courtesy of Andrew Emmerson

The second stop here was at a spot where Asian Crimson-winged Finch (pictured above) are attracted to a particular rocky slope by salt put out by shepherds for their goats. There was a bit of a wait this time before a pair flew in and again I was unable to obtain pictures. This generally shy Finch also occurs from this area of Turkey south-east to Pakistan in montane habitat. It inhabits rocky slopes often at high elevations, nesting in crevices and ravines, but moves lower down in winter. A separate population in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains was formerly considered to be con-specific but in 2011 the two were split into separate species.

That montane speciality was soon followed here by another in White-winged Snowfinch (pictured above). This was a very welcome lifer indeed as I have not previously visited likely places for them. The best chance of seeing them closer to home is said to be around rubbish skips in Alpine ski resorts. The species ranges at high altitude from the Pyrenees across southern Europe and into the Middle East.

Black Redstart, Red-billed Chough and Egyptian Vulture were also noted at this site. Our guide was then excited to locate a bonus bird Pale Rock Sparrow / Finch (pictured above), the first one ever seen on this tour. It is a summer visitor to parts of the Middle East and Central Asia that is rarely found so far west. And this sighting completed a to say the least, rather special morning session.

Now we visited the aforementioned Sultan Marshes, taking lunch under cover as the heavens opened. After the downpour ceased we braved the sodden board walks and soggier wet meadows into and around a large reed-edged lake in search of what for me were two further huge lifers. Moustached Warbler and White-headed Duck owed that status to being two of just six remaining stragglers on my south-western Europe wish-list. Now that number is four: those being Eastern Olivaceous and Orphean Warblers, Crested Coot and Lammergeier.

I had previously failed to find Moustached Warbler in areas where they were said to be in Cyprus and la Camargue, France. Now I fully appreciated why as they are easy to hear but extremely difficult to set eyes upon. As tour colleagues called the bird all around me I remained optimistic or naive enough to assume they must actually be showing, but of course it was only no longer visible glimpses that were being referred to. This was all very frustrating and as we walked on to hides at the boardwalk’s end my tolerance level deteriorated.

There are two pairs of White-headed Duck at this site, and after a short wait a female was spotted on the far side of a large lagoon. Gradually but steadily she moved towards our hide. There is a very small population in southern Spain that I didn’t get around to visiting on my only solo birding trip there. The Spanish cluster was responsible for the English Ruddy Duck population being eradicated earlier in this decade, since it was considered males of the latter persuasion were rather too intent on holidaying on the costas and inter-breeding with the native White-headed females. It was a culling programme that remains a matter of great controversy amongst British birders.

Now I had my opportunity to record this long sought item, but when our individual was only half way across the lake my fellow tour participants decided to move on. It was now that I rebelled against the group as I have been told I am wont to do, and no problem there. I am not a photographer either but I did want at least half-decent pictorial records as well as a trip list addition. So I stayed behind and the female WHD edged nearer and nearer before crossing in front of the hide and the above images were gained. But neither resident male chose to show itself on this occasion. I must confess to not quite getting it why anyone would have wished to leave in the circumstances.

Satisfied with the experience, I moved back along the boardwalk to where the Moustached Warblers had been active, enjoying my re-established independence. Hanging around there for some time I gained just one diagnostic view that revealed the boldly striped head pattern, such as I wanted. That had to suffice and at length I strode on to catch up with the group. In the wet meadows Squacco and Purple Heron both stood out in places. The latter is a water bird I had managed to take pictures of just once previously, on Cyprus’s Akrotiri peninsula in April 2012. These digiscoped images (below) are a little better.

When I eventually re-joined the group I had apparently missed Citrine Wagtail and distant Lesser Short-toed Lark, neither of which I needed on this tour. But I had noted an unusual Wagtail of some kind as well as Spur-winged Plover. After leaving Sultan Marshes behind we drove on to our overnight stay at the excellent Pansiyon Safak (see here) in a village Çukurbag on the other side of the Aladaglar Mountain range from where we had been earlier. In the morning we were to be taken up Mt Arpalik Çukuru (below right) for the climax of this tour.

Day four (19th); Aladaglar mountains (other side – a), Emli Valley (b)

a – Caspian Snowcock (15), Chukar Partridge, Crimson-winged Finch, White-winged Snowfinch, Red-billed and Alpine Chough, Crag Martin, Red-fronted Serin (16), Radde’s Accentor (17), Ortolan Bunting, Horned Lark, Finsch’s Wheatear (18)

b – Syrian Woodpecker (19), Scops Owl, European Bee-eater, Red-backed Shrike, Blue Rock Thrush, Chukar, Isabelline Wheatear, Alpine Accentor

==============================

Pensions are family run guest houses offering basic but wholly adequate accommodation at low cost to travellers with outdoor interests. I thought the ambience was entirely suited to a trip such as this. Our host Hasan (of apparent Gosney fame) owns a tractor and trailer with which he transports his birding, trekking and mountaineering guests to high elevations. It was an exhilarating ride, our mission being to observe one of the rarest and most tricky to observe birds in the Western Palearctic, Caspian Snowcock when they become active on the mountain tops at dawn around 5:00 am.

Soner was impressed by nobody being late for the tour’s pre-breakfast sessions, though he did warn that any transgressor would not be waited for. Today’s was the earliest start of all at 3:30 am and wearing our extra packed layers we duly reached the darker and lighter dividing line in the preceding picture to scan the towering rock faces above. I was actually the first to locate our quest, just about the only bird I called all week.

The group scanning for Caspian Snowcock on Arpalik Çukuru

Caspian Snowcock are hefty grey-buff toned partridges that are native to scattered mountain areas from this part of Turkey eastward, and from Armenia and Azerbaijan to south-western Iran. They favour steep, inaccessible locations at altitudes from 1800 to 3000 metres, in which they are very wary and difficult to approach. Further north the related Caucasian Snowcock is endemic to the Caucasus region.

Caspian Snowcock (above) © rights of owner reserved

We gradually became aware of these birds’ far carrying, ascending, whistling calls, that are said to resemble Curlew, from around five locations. The plumage is patterned grey, brown, white and black, but looks pale grey from distance. The Snowcock were very well camouflaged against their rocky habitat but through scopes it was not difficult to discern their movements. Chukar Partridge were also calling in places, while Red-Billed and Alpine Chough and Crag Martin were active overhead.

I was able to send and receive texts from this elevation despite being outside my network’s EU range. Having converted the early morning’s prime target so successfully we then turned our attention to the montane passerine life of these high slopes. Crimson-winged Finch (pictured below, left), White-winged Snowfinch and Ortolan Bunting were all active here; as were two more important target species of the region.

Radde’s Accentor (above right and below left) is resident here and in the southern Caucasus, and a short distance migrant in between. This is a lively and restless little bird, that flies between low bushes and scampers on the ground, rarely staying in one spot for long. Dunnock sized, it more closely resembles Alpine Accentor but with a striking head pattern of broad, cream, supercilium, whitish throat and dark crown and cheeks. It inhabits boulder strewn, scrubby areas between 2500 and 3000 metres, and is prone to wing flicking as it darts around.

Red-fronted Serin (above right) was as restless and mobile but the males stood out by their very dark, sooty head pattern. I nonetheless gained only several glimpses and could not get pictures. This little finch is a breeding resident in mountain regions across Turkey, the Caucasus and Iran, occurring between 2000 and 4000 metres. And thus my set for the tour of small regional passerines that are unlikely to be encountered further west was complete. It had required a deal of effort and determination to acquire all these early morning sightings on this day, but we had been almost totally successful.

On the drive back down the mountain we encountered first Horned Lark then a further absentee from my Cyprus list, Finsch’s Wheatear. The latter is most easily told apart from the similar Black-eared and Pied Wheatears by a broad white band that runs all the way down its back. Here we came across an adult and juvenile together.

One species that had eluded us so far was Syrian Woodpecker, the last European member of that genus I needed for my life list. After a late breakfast back at the pension we set out to find one in nearby orchards such as the species favours over denser wooded areas. I was able to gain a good view of the perched bird that is very difficult to tell apart from Great Spotted Woodpecker, so I am just taking our expert guide’s word for the ID.

The other peckers we found on this tour were all Middle Spotted. Having read things up I understand the clearest diagnostics for Syrian by comparison with GSW are an incomplete black cheek band and lack of black at the base of the bill, as this outsourced picture (below) shows. The “tick” call is also softer in Syrian, whose drum roll has longer pauses. European Bee-eater was also located at this site.

Syrian Woodpecker © rights of owner reserved

This location opposite the Safak pension is on a track that leads up into the Aladag National Park via the very scenic Emli Valley (pictured below) which we now explored further. Our guide said conditions were not good for Lammergeier, my only remaining trip target. So upon coming across concentrations of mud puddling blue butterflies containing several new species (for me) that I just could not walk past, I followed my own agenda for a while. When I rejoined the group I had apparently missed Golden Eagle and a distant Rock Sparrow, but no matter.

A short afternoon rain break then ensued after which we walked back. Alpine Accentor, Blue Rock Thrush, Red-backed Shrike, Isabelline Wheatear and more Chukar Partridges were all now recorded, and we inadvertently disturbed my second ever Eurasian Scops Owl. But the Red-throated Serin that we hoped for better views of here were just not playing ball. After that pre-dawn start to the day and having foregone lunch we returned to our accommodation early for rest and relaxation. It had been a memorable day.

Day five (20th): Turla Wetland (a), drive to Adana and airport (b)

a – Cattle Egret, Pygmy Cormorant, White-throated Kingfisher (20), Black-crowned Night Heron, Squacco Heron, Pied Kingfisher, Graceful Prinia, Kentish Plover, Little Stint, Spur-winged Plover, Avocet, Caspian Tern, Little and Sandwich Tern, Booted Eagle

b – Collared Pratincole, White-spectacled Bulbul (21)

==============================

Our return flight from Adana was not until late afternoon, which allowed plenty of time to visit some coastal sites en route to that town’s airport and add some wetland birds to the trip list. Regional favourites Squacco and Black-crowned Night Heron, Pygmy Cormorant and Cattle Egret were all observed in drainage ditches and along canals while raptors including Booted Eagle soared overhead. But the real prize here were the Kingfishers.

White-throated Kingfisher, my 20th trip lifer that occur here at the far western end of an extensive geographical range, are impressive looking beasts indeed. The size of a large thrush, this lively, vividly coloured bird is not strictly associated with water but can also be found on drier farmland and in woodland or town parks. We observed them mainly on overhead wires.

After a heavy though thankfully brief shower we moved on to a site Turla Wetland for a three hour stay. There we soon located the as wide ranging Pied Kingfisher that was especially satisfying for me. The status of Greater Short-toed Lark on my life list having been clarified earlier on this trip, PK was probably the last bird therein about which all doubt needed to be removed. Of the several records I submitted to the Cyprus bird recorder following my first trip there in November 2011 this was the only one I wasn’t sure about, but also the only one that was accepted. I have been known to mention that in this journal from time to time. Now I had a nailed-on, unmistakable sighting.

The bird we watched here was in exactly the pose replicated in the outsourced picture (above, left), and also treated us to a display of hovering as this Kingfisher is wont to do. Graceful Prinia were observed here for a second time on the tour, offering better views than the first but still beyond camera range. Waders included Kentish Plover, Little Stilt, Avocet and Spur-winged Plover (above right); while Caspian, Little and Sandwich Tern were all noted.

It remained to do justice to White-spectacled Bulbul. Also known as Yellow-vented Bulbul this resident species across coastal regions of southern Turkey, then south to the Red Sea and around the Arabian peninsula, is especially plentiful in the Adana area. We had noticed them dropping off roadside wires or landing in trees from time to time during the tour, but without ever seeing them well. Now, on the final drive to the airport that situation was rectified (pictured above); and that was my 21st lifer for this trip.

Conclusion

This was quite simply a fantastic tour. I was attracted by the potential for upwards of 17 lifers and in the event 21 were delivered. The majority of those were western Palearartic species on the edge of their range such as birding this region affords the opportunity to experience. But I also knocked eight lingerers off my dwindling south-west and south-east European wish lists, albeit that these were recorded outside those political boundaries. My only trip target to evade us was once again the elusive Lammergeier … one day, maybe I will see one.

It was also an agreeable group, free from non-stop talkers, wisdom dispensers or stand-up comics; and with a good range of ages. As a party of 10 we travelled in a comfortable and spacious 16-seater minibus instead of the cramped and vision restricted 8-seaters used by so many other wildlife tour operators. Turkey was an interesting and scenic country to visit, especially in the mountain areas. The food was good, healthy and never too much of it; and I found Turks on the whole to be friendly and hospitable people who do not seek to exploit foreign visitors to their country.

In short I can thoroughly recommend Wildwings’ package and especially our leader and guide, the incomparable Soner Bekir and his trusted Captain who did all the driving. Thanks again guys, you were superb. My WestPal bird list now stands at 489.

For the full species list of 161 birds for this tour see here.

Estonia: 5 – 10 April 2017

Having experienced most regular (ie non-vagrant) birds in south-west Europe over the last five years, my attention in 2017 turned to new countries in which I might gain multiple life list additions. One of these is Estonia, the most northerly and least populated of the Baltic states. Hence I joined this group tour by a Dutch operator BirdingBreaks.nl that was featured in Birdwatch magazine. The trip targets were mainly woodland species: three Grouse, three Owls, Nutcracker, and very importantly four new Woodpeckers; as well as Eagles and the sea duck Steller’s Eider.

One landscape predominates in northern and western Estonia: flat, mostly yellow-toned fields and tracts of predominantly pine, silver birch and spruce woodland. This region, having been shaped by the ice ages is further characterised by peat swamps, lakes and river flood plains, and nowhere exceeds 50 metres above sea level. The pictures below give the general impression. It is endlessly samey, dour even but very wildlife rich.

About half of the country’s surface area is wooded. 25% of this is protected with a larger proportion given over to commercial forestry. But timber was not exported during the 20th century Soviet occupation so there are a lot of trees to go round. All of this poses the question of just where to start looking for the required woodland birds. I think it would be very difficult to bird this country alone, or even in a group without a local guide.

Day 1: We set off from Tallinn airport by minibus at around 2:30pm on 5th April, our destination being the island of Saaremaa. The first stop along the way was Kasari floodplain meadow, one of the largest extant open meadows in Europe. Flooding is caused here by snow melt in the catchment area and strong south-westerly winds that push sea water onto coastal lowlands. At the time of the spring flood thousands of migrating wildfowl stop over here, and as the waters subside the meadow attracts large numbers of waders.

Scanning the Barnacle and White-fronted Geese we found two Red-breasted Geese in amongst them. This was a good scene setter for northern birding I thought.A White-tailed Eagle made a long and languid fly past, then another one drifted through at greater distance. These huge raptors that have a front-heavy, large-billed, long, broad-winged profile with deeply fingered primaries, were seen on every day of the trip.

From time to time along our route Common Crane would adorn roadside fields, almost always in pairs and sometimes dancing. A lot of these long-distance migrants pass through Estonia in spring time to breeding grounds further east. But Estonia’s bogs, swampy forest openings and wetlands are ideal breeding habitat so a proportion remain here. They were a frequent sight throughout this trip. The calls of these stately, long-legged birds as they approach in the air was also the week’s most evocative sound.

On the ferry crossing to (and from) Sareema what seemed a roll call of northern wildfowl would drift by on either bow, or fly busily from one spot to another. Long-tailed Duck were everywhere. There are thousands of them in the northern Baltic. Common Scoter were well represented, while the white eye and wing patches of a few Velvet Scoter could also be picked out in some of the rafts that rode the waves in the middle distance. Also seen in varying numbers were Scaup, Common Eider, Common Goldeneye and Red-breasted Merganser. It was impressive to see all these ducks in such numbers and a different birdscape from other parts of Europe certainly.

Long-tailed Duck courtesy of Richard Stansfield

Before reaching Saaremaa the road crosses a smaller island Muhu. Between the two is a narrow strait which is traversed by a causeway. Offshore here were very many Bewick’s Swan and also numbers of the larger Whooper Swan, as well as Mutes. In amongst these were more familiar wildfowl such as Tufted Duck, Wigeon, Teal, Gadwall, Northern Pintail and Mallard; and also Smew here and there. But the must-see attraction of this island is the wintering flocks of Stellar’s Eider which grace it’s western seaboard that is ice free all year round, Those would have to wait for the morning.

Day 2: Our overnight stay was in a former manor house dating from the German occupation of Estonia in centuries past. These facilities, once the homes of foreign nobility, are now state owned and leased out to local hoteliers. On Thursday morning we headed for the coastal national park of Vilsandi that covers a total area of 237.6 km sq comprising many islets, peninsulas and relatively sheltered bays.

It is the last-named that attract around 2000 Stellar’s Eider from December to mid-April. They have to be picked out from amongst their Common cousins and the ubiquitous Long-tailed Duck here, as well as the assortment of wildfowl noted on day one. The tundra breeding Stellar’s prefer shallow coastal waters in winter, especially with in-flowing fresh water, and they often come quite close inshore.

Our guide checked out a number of likely locations without success, before we arrived at a rather remote and deserted jetty location in Kudema Bay. This internationally Important Bird Area (IBA) is an important staging and wintering area for many water fowl. Here we scanned through the by now familiar assortment of offshore duck until from right at the end of the jetty a raft of about 80 or more Stellar’s Eider (lifer) were located bobbing in and out of view towards the far side of the bay.

Raft of Stellar’s Eider in Küdema Bay

These birds are about two-thirds the proportion of Common Eider, roughly the size of Common Goldeneye. Steller’s have a square head and spatulate, not wedge-shaped bill. The body appears elongated and the tail is cocked upwards like a Scoter when at rest. The stunning males are intricately patterned though at a distance stand out as almost white amongst the dark, chocolate-brown females.

We all observed them for some time before it was time to move on. I was one of the first back to the minibus but was then called back. Our raft of duck had relocated much closer inshore and so the diagnostics were plainer to see, especially with the pale-toned drakes. And so we watched a litle longer before departing.

There was now a long drive south-eastward to Soomaa National Park. On the way we stopped at a woodland site where the first of the trip’s woodpeckers was located. Grey-headed Woodpecker (lifer) occurs across much of northern, central and eastern Europe, southern Russia, China and south-east Asia. This medium-sized woodpecker feeds mainly on ants and other insects, and so requires habitat with plenty of insect-rich decayed, deciduous trees. Hence this species has declined in areas where old natural woodland has yielded to commercial coniferous forestry. Plumage is similar to the larger European Green Woodpecker with the obvious difference of a grey instead of green head and a red forehead patch in the male. It has a shorter neck, slimmer bill and slightly rounder head than Green Woodpecker, and lacks the latter’s black and white bars on the tail sides.

“Soomaa” in Estonian means land of bogs. 80 per cent of the park’s 390 sq km area consists of raised bogs, swamp forests and seasonally flooded meadows that are largely untouched by human activity. This area’s river system cannot hold all of the waters flowing down from neighbouring uplands in spring, and so roughly half of it floods in what is known locally as “the fifth season”. At this time the steep-sloped raised bogs of what is Europe’s largest intact peat bog system stand like islands in expanses of water.

The map above shows the main raised bog areas between which run roads on higher ground. Western Capercaillie lek in the early morning at the bog margins and then frequent the roads where they take grit into their gullets to aid digestion. Hence these large gallinaceous birds can be rather easier to experience here than has been suggested to me by other Oxon birders’ accounts of their Capercaillie encounters in the Scottish highlands. And the swamp forest habitat holds eight species of Woodpecker.

Day 3: Our accommodation for the next two nights was a guest house where each participant (we all travelled solo) had a very pleasant, twin-bedded chalet room with splendid bathroom. There are clearly very good low season deals to be gained in Estonia and the food is superb. Setting off early to explore the national park on 7th April, we stopped to survey a flooded area holding large flocks of Eurasian White-fronted Geese and Bewick’s Swan with some larger Whooper Swan mixed in too. I regard this sequence (below) as possibly the most evocative images that I brought home from Estonia and those most suggestive of birding here.

Our second stop was with the express intent of observing woodpeckers. At this location we were rewarded with good views of three species: White-backed, Lesser Spotted and Black Woodpecker. The biggest one and the little one were each found once more later in the week, but this was the only trip sighting of White-backed Woodpecker, the second of the four Picidae lifers that I so wished to gain in Estonia. This species has a similar range geographically to Grey-headed Woodpecker. Since it feeds on wood boring insect larvae, large tracts of wet deciduous forest with plenty of standing or laying dead or dying wood are required. The biggest of the spotted western Palearctic woodpeckers, its plumage has the same colours as the slightly smaller Great Spotted Woodpecker but with stand-out white bars across the wings and a white lower back. The head profile is more angular and the bill longer. Males have a red crown and females a black one.

I had seen a Black Woodpecker once before, in Belgium two years ago (see here). This largest of the Palearctic peckers inhabits mature pine, beech and mixed forest throughout mainland Europe. It is a bit of a brute of a bird with a rather clumsy, flappy flight pattern, though what to me is a slightly comical jizz and engaging manner. Crow-sized, it flies on a straight course with head held up and mostly downward beats of broad, rounded wings. Being inquisitive in nature, this bird can be called up easily using recordings. I will admit that most of the woodland trip targets were attracted in this way. I appreciate that not all birders agree with such practice, but our guide’s view like my own is that not much disturbance can result if things are done in moderation. When the second of our two Black Woodpeckers was summoned it made several passes of the group and one of my colleagues captured the image above right.

We next took a road between two adjacent areas of peat bog in the east of the park. This is a known morning location from about 8am for Western Capercaillie, and we were rewarded with good views of three hens. I had made sure I got the front passenger seat of the minibus and so was able to capture possibly my best image of the week (below). Everyone remained inside the vehicle as is essential when observing large grouse.

Western Capercaillie (fem)

This is the world’s biggest grouse species, though hens typically weigh about half as much as the cocks. Our guide told how they are a familiar sight on or beside roads through suitable habitat, mature coniferous forest in Estonia. At one time this species could be found across all of Europe’s northern taiga forest. But they have declined in proportion to woodland with diverse tree composition and a relatively open canopy structure being converted to dense, commercial forestry plantations.

Later in the day we explored more swamp forest sites, including the Beaver Trail from the Sooma National Park visitor centre that takes visitors into areas containing Beaver lodges and dams. Here I gained what for me was an important lifer and a bonus bird for the trip: Lesser Spotted Eagle. This medium-sized migratory raptor winters in sub-Saharan Africa and breeds across central Europe including the Baltic states. They prefer undisturbed, well-structured deciduous forests mixed with wet meadows and swamps such as Estonia offers. But only small numbers occur here.

This sighting’s significance is that I had encountered the related (Greater) Spotted Eagle wintering in France’s La Camargue just over a year ago (see here). Local birders there explained how hybridisation occurs between the two species, about which there are very detailed taxonomic issues. So now I have expert assurance of having observed examples of each.

Day 4: Leaving the swamps of Soomaa behind we now headed for the north-western coast of Estonia, west of the capital Tallinn. Our first stop on the road was a manor park Elurikkus Parkides that has a resident pair of Middle Spotted Woodpecker. There is even a picture of one on the information boards here. Our guide succeeded in calling up the male at the first attempt. This noisy, inquisitive bird buzzed about for a while before seeming to suss out that there was no intruder on his patch, just a bunch of tourists with a recording. Then he flew disdainfully away. So that was the third of the Picidae lifers gained. © rights of owners reserved for each of these outsourced images (below).

This insectiverous bird feeds mainly in the canopy, moving constantly and so is usually difficult to observe. It is only negligibly smaller than Great Spotted Woodpecker but the size difference is accentuated by Middle Spotted’s more rounded pale head and slender bill. The main plumage differences are a red crown, lack of black moustachial stripe, a pink vent and dark streaks on the flanks. This species occurs across central Europe and is at the northern edge of its range in the Baltic states. It favours deciduous woods with a mixture of clearings, pasture and denser parts.

Goosander (pictured above) were encountered often throughout this trip and one pair at this location provided a good photo opportunity. I rather like the flight shot (bottom left), one of my better and luckier efforts of the week. The small passerines here included Crested Tit and the northern race of Long-tailed Tit (both pictured below). Hooded Crow (right) are also common in Estonia.

No birds of significance to me were encountered through the rest of this day during which we visited coastal wetlands and more forest sites. Late afternoon we arrived at our third base for the trip Roosta Holiday Village, where the standard of accommodation went off the top of the scale. Each participant had a holiday lodge to themselves, that for me was like a park home from home. Then in the evening we finally caught up with Eurasian Pygmy Owl (lifer) after four nights of trying.

Our guide had seen this first of the Owl trip targets often during March but explained that they were breeding early this year and so the males fall silent. The likelihood of seeing them is also affected by the age mix of owls occurring in the field, since younger males seeking mates are more vocal than more mature, established individuals. Tonight’s bird was also attracted by a recording, making several passes of the group and perching in tree tops; a diminutive, Starling-sized silhouette, round-headed and diamond shaped in flight.

Day 5: On our final day in the field we set out early to search for the three Grouse trip targets. There are multiple Black Grouse leks in the area around our base and we viewed some of these rather distantly. Hence this was a rather watered down experience compared with my observation of lekking Black Grouse in north Wales a year ago (see here). What I hadn’t seen before was the females waiting to avail themselves of the winner. These hens (below top right) had chosen a grandstand view of proceedings.

En route to viewing these leks we encountered two male Western Capercaillie along one road, by any standards impressive birds. Cocks typically range from 74 to 85 cm in length and an average weight of 4-1 kg. The largest wild cocks can attain a length of 100 cm and weigh up to 6-7 kg. They are strongly territorial occupying a range of 50 to 60 hectares. The fuzzy picture below was taken through the dirty, tinted windscreen of the minibus but conveys the general impression.

Western Capercaillie (male)

The third gallinaceous bird on our wish list was the Jackdaw-sized Hazel Grouse. These occupy the same geographical range as Capercaillie in taiga forest across northern Europe and western Asia. They prefer damp and densely undergrown areas with old tree species, spending much time on the ground, but may walk along the limbs of trees. Hence they are usually difficult to see and we were unsuccessful in our two days here, merely hearing the whistling call of a Hazel Grouse once. This bird is most likely to be seen flying across the road ahead.

While searching suitable habitat for the elusive Hazel Grouse we came across two more trip targets. Spotted Nutcracker (pictured above) is a bird I have seen once before in Liechtenstein in 2009. This Jay-sized species occupies an extensive range in taiga forest from Scandinavia across much of northern Europe, as well as mountain conifer forests further south. The voice is loud and harsh. Once called-up by our guide, today’s pair took a good look at the group from several fly-pasts, before seeming to decide that we posed no threat and moving on.

Next we gained the fourth and final trip Woodpecker that I came here to put on my life list. Three-toed Woodpecker (pictured below) is resident in coniferous and mixed forest across northern Eurasia. This shy, dark looking species is insectivorous, feeding mainly on wood-boring beetle larvae. Just a little smaller than Great Spotted Woodpecker, Three-toed is black on the head, wings and rump; and white from the throat to the belly. The back, flanks and tail are barred black and white. The adult male has a yellow cap.

A second birding group from Germany was also staying at our base, and their guide knew of a Ural Owl nest site in the vicinity. So having been briefed, our guide went to reconnoitre then took us to see the bird in the evening. This is a very large owl though not as big as European Eagle Owl, that breeds in old bog forests. All we could see at the nest site was the top of the female’s round head quietly contemplating her surroundings, and her tail protruding from the rear of the nest. Keeping an appropriate distance at all times we waited for around 90 minutes for the male to return and do a changeover but this didn’t happen. Being a breeding site there was no question of using a recording to further our objective. Eventually our guide advised that the male’s absence could be due to him being aware of our presence, and so we left.

We had now gained almost all of the trip targets. The exception was Tengmalm’s Owl that has suffered a recent population crash in Estonia. As we left our base to return to Tallinn a Hazel Grouse flew across the road in front of the minibus, almost colliding with the windscreen. I didn’t see it being seated behind the front passenger seat that was occupied by one of the biggest of my tour colleagues. He said the bird could have been anything. So I had gained nine life list additions over these five days: Steller’s Eider, the four new Woodpeckers, Pygmy and Ural Owls, Western Capercaillie and that Lesser Spotted Eagle.

Fuerteventura: 22 – 28 February 2015

I was inspired to do this trip by Oxonbirder Peter Barker who made me aware of the destination a year ago. This most arid of the Canary Islands offered 12 possible life list additions (denoted by *), many of them North African species that occur offshore here. I gained 9 of them. Fuerteventura is fairly well documented in on-line trip reports and I consulted some of the more recent of those on Fat Birder to research sites to visit. Peter also lent me his copy of Clarke and Collins that though published 19 years ago is still regarded as the best available guide book.

Caleta de Fuste area

As I envisaged, my chosen base for the trip is a purpose built, high density tourist resort surrounded by much emptier arid land. I set aside day 1 on 22 February to explore the immediate area and see if I could find any of the trip targets here. I first walked around the nearest open space to my hotel without seeing any birds at all, and then explored the resort itself that took just half a day. I usually like to start a trip with a walking day but it was clear that the landscape here would be too vast and samey to see much wildlife on foot.

After lunch I took a longer walk to the south-west. Southern Grey Shrike * was the first of the trip targets gained and there were Ruddy Shelduck on one of the golf courses. After heading inland a little I cut across dry stony land back towards the FV-2 coast road and soon began to see Berthelot’s Pipit *. This Canary Islands and Madeira resident became a common sight throughout this trip.

I walked out as far as Salinas del Carmen where there is a salt pan museum but not much in the way of birds. A lot of Barbary Ground Squirrel were active there, running right up to me since they must be used to people feeding them. The entire island population is apparently descended from two animals imported as pets in the 1960s.

On the homeward walk I found a very smart Little Ringed Plover, then met a couple birding who pointed out more common waders – Redshank, Greenshank, Whimbrel and Common Sandpiper – in a drainage gulley alongside one side of the Elba hotels. I revisited this spot on my final morning 28 February, photographing a new (for me) dragonfly Lesser Emperor at the coastal end of the same gulley.

Barranco de la Torre

This site, just to the south-west of CDF is in all the sources I researched, particularly as a reliable location for the endemic Fuerteventura Chat. Clarke & Collins cites an access track on the FV-2 beyond Las Salinas so on 23 February I looked for that first. It is now a metaled road leading to a dam construction site. There were unwelcoming notices around the works entrance so I found a relatively easy descent into the barranco to the north-west (pictured below) and walked upstream from there.

The dried out water course held the chat breeding habitat of Tamarisk scrub, but although there were plenty of bird sounds coming from cover most of those visible were Spanish Sparrow. That abundant species became the “oh no not more of them” bird of this trip but they were always fun to watch. I sat in a promising looking spot to see what might emerge and heard the sound of raptors calling from the southern side of the gorge.

Two Egyptian Vulture * then drifted right over my head, circling above me showing their colours well before continuing northwards. I could not have hoped for better views of what is a huge lifer, this bird having been missed on both my South of France trips in recent years. On the return walk to the car I encountered a first pair of Trumpeter Finch * amongst more Spanish Sparrow around a ruined building. Ruddy Shelduck flew overhead a number of times.

In the afternoon I investigated the southern end of Barranco de la Torre, into which a dirt road runs from the coastal track south of Las Salinas. This was a pleasant walk below a cliff face (pictured above) and I was quickly into the same habitat as in the morning. There was a lot of sound coming mostly from cover again until I reached an area teeming with bird life especially around one enclosure. There were lots of Spanish Sparrow and Trumpeter Finch here, a few Spectacled Warbler, Berthelot’s Pipit; and briefly and into the sun a perched good candidate for Fuerteventura Chat. I hung around here for some time but didn’t see the last-named again to remove all doubt.

When this burst of activity subsided I continued along the Barranco. The dirt road fairly soon turned up to a farm, and at the start of a northward track was a notice saying the next stretch of the Barranco is closed to the public during the bird breeding season commencing 15 February. I was respectful as usual and turned back, which was a pity because that must have been the best area for birds. On the return walk I spotted a Southern Grey Shrike on the cliff top, PI’d Lesser Short-toed Lark for the first time and picked out another distant Vulture to the north.

On 26 February in the late afternoon I checked out the upper part of this barranco where it is crossed by the FV-2. I walked along the dry river bed back towards the construction site, finding a dragonfly that looked like an Epaulet Skimmer. There was a lot of bird activity in the dense Tamarisk scrub here with Spectacled and Sardinian Warbler and Blackcap all active.

Barranco de Rio Cabras

Clarke and Collins describes this second barranco where Fuerteventura Chat occurs, immediately north of the airport. The book says in the past twitchers have been known to fly to this island just to see its only endemic in this location then go on their way. It is reached by leaving the NV-2 at Playa Blanca then turning back along a dirt track to close to where the NV-2 crosses the ravine. I first went here on 24 February.

At this Barranco’s eastern end (pictured above) there was little bird activity but I kept walking right up to an old dam. Immediately before the structure there was standing water and things began to get more birdy, starting with several White Wagtail. At the dam itself a pair of Fuerteventura Chat * were active: mission accomplished but much more was to be revealed.

The presumably disused and partly overgrown reservoir at the top of the barranco was a hidden gem of a place and teeming with wildlife. There were Black-winged Stilt, Greenshank, more Ruddy Shelduck, Southern Grey Shrike and numbers of the familiar small birds of the trip so far. What I took to be Barbary Partridge* were calling from the cliff faces, one on either side. And in the late afternoon sun large numbers of Sahara Blue-tail, the Canary Islands’ only breeding damselfly were flying.

- Fuerteventura Chat

- Above the dam

- Fuerteventura Chat

- Southern Grey Shrike

- East Canary Skink

- Trumpeter Finch

This was the sort of location in which I feel in my element: remote, way off the beaten track and only me and the wildlife there. The nice warm feeling grew in me that I had enjoyed so much in many southern Portugal locations last May. On finding it was 5pm I started a brisk return walk and one of the Chats was back on territory as I passed the dam wall again.

Having found this place so fascinating I returned the following afternoon. The Chats were once again active at the dam but things were generally less birdy than a day earlier. I was hoping to get better views of the Barbary Partridges but didn’t hear any this time. But in the afternoon sunshine I did find the trip’s first dragonflies: first a fly-by Emperor species and then some Scarlet Darter in the highest part of the barranco. The SBTDs were flying in their hundreds.

In each of the barrancos that I visited to the south and north of CDF there were many small, fast flying and mostly very worn yellow butterflies. These were Greenish Black-tip, a species that ranges from the Canary Islands across north Africa and the Middle East as far as Turkmenistan and Pakistan. I also saw this insect in most parts of Fuerteventura that I visited.

- Worn Greenish Black-tip

- Sahara Blue-tail Damselfly

- Broad Scarlet (imm)

El Cotillo

A stony plain between Tindaya and El Cotillo in the north-west corner of the island is reputably one of the most reliable spots for Houbara Bustard *. This Fuerteventura must see is a race of a much declined desert species that occurrs across north Africa and as far east as Jordan. On my first visit here on 24 February I was accompanied by English birders Chris and Rowan Whiffin from Basingstoke, who were staying in my hotel.

Near the start of a dirt road from El Cotillo a notice bearing an image of a Houbara requests that visitors keep to the main track. Using the car as a hide is the recommended strategy in all published sources. We saw just one Houbara at reasonable distance, located by myself about 500 metres before a high point that I understood to be a hot spot for them. It is said that with luck birds may cross the road in front of observers, but we were not so lucky.

Shortly after the Bustard sighting two Black-bellied Sandgrouse flew around the area in which we were parked offering several excellent views. Once they flew right above the car, such a contrast to my failed attempts to find Pin-tailed Sandgrouse on the plain of La Crau in Provence. Both this day’s birds were lifers for my companions who were very pleased with their morning out and guide. But we could not find Cream-coloured Courser here despite much scanning, just a succession of rocks impersonating this further must see. We followed the dirt road as far as the Barranco de Esquinzo and then turned back, though it was possible to continue as far as Tindaya.

I returned here two days later on 26 February at dawn when the speciality birds are said to be more active. Driving slowly southwards along the same rough coast road, I saw nothing in the first hour. When the sun rose at 8am over the hills to the east Berthelot’s Pipit and Lesser Short-toed Lark immediately became active. Whilst trying to locate some of the latter on the ground I picked up what looked like a big white feather duster being blown through the steppe. Then it became still and turned into a blob. This had to be a displaying male Houbara so I retrieved my scope from the car. The blob then raised its head showing the long dark neck stripe of the Fuerteventura race, while the white display feathers hung down to one side. I had indeed seen what visiting birders seem to regard as a prize: a displaying male Houbara Bustard, but only briefly before the bird disappeared once more into the steppe.

At just after 9am on the return drive to El Cotillo I suddenly saw a pale shape running through the steppe to one side of the road. This was at last my Cream-coloured Courser * for the trip and a wave of relief swept over me. After much time in the previous two days spent checking piles of rocks randomly to see if anything was moving, I was surprised by how easy this bird was to see in the end. It stood out plainly from the habitat as it continued to move about, standing with head cocked at times. In terms of hugeness as a lifer, CCC was second only to Egyptian Vulture for this trip. That’s because it was absent from my Cyprus list, and a couple of years ago I considered a golf course in Shropshire too far to go to see one that turned up in blighty. I would not make that decision in the latter instance now.

I left site at 9:30am without having met another car on the track. I could have stayed here all morning just driving around slowly hoping for more sightings but having achieved a double result decided to content myself with it. These birds are clearly difficult to find and I was also mindful of being in a hire car that was not insured on dirt roads. Chris and Rowan who hired their own car on this day said they came here again in the afternoon and saw nothing. With such a good CCC sighting after so much searching I felt little inclination to scan more stony plains at random across the north of the island.

Other sites and missed birds

A reservoir at Los Molinos on the western side of the island is cited as a prime birding location in all the sources I researched, being the only one with permanent water. Visiting here on 25 February I couldn’t find the southern way in as described in Clarke and Collins. I then drove to the dam end along a rough road from a village Las Parcelas on the FV-221 road. All I could see from the dam were gulls, some Ruddy Shelduck and Eurasian Coot. A school party engaged in what appeared to be a botany lesson had probably seen off any passerines in the vicinity.

Access tracks beyond this point were fenced off so it was not possible to get down near the water’s edge where common waders may be seen. In short I couldn’t see why other birders bother to come to this site, unless they want to build a trip list. Plainly I would not see anything new here, and so I drove slowly back along the access road scanning around fruitlessly for Cream-coloured Courser. This was very noticeably the most arid area of Fuerteventura I had experienced (pictured below).

After nailing CCC the following day, I consulted my sources to see where the remaining four birds on my wish list might be found. Laughing Dove and African Blue Tit were described as garden and forest birds. Returning homeward via La Oliva I drove through an area just north of that small town that looked ideal habitat. So I spent a hour walking around an area of gardens and small enclosures that was a pleasant contrast to the wild and arid areas most of this trip had involved.

There were a few Tits flying around here, so I ticked African Blue Tit * on the grounds of it being the only Tit species in the Canary Islands. Corrrect me if I was wrong to do so anyone. Other birds seen here were Hoopoe, Blackcap, another pair of Fuerteventura Chat and the inevitable Spanish Sparrows. Also in La Oliva I encountered this rather handsome lizard (pictured below). I just love ‘em!

On 27 February, my last day with the car I checked through the trip reports and two things stood out: the prospect of Plain Swift around the CDF golf courses, and an Egyptian Vulture site along a dirt track east of a village Tiscamanita to the south-west. I started with the golf courses, seeing no Swifts of any variety. Then I drove on to Tiscamanita that is on the FV-20 road south of Antigua. I followed the dirt road into a scenic area (pictured below) until it became a bit too rough for my liking then turned back. Above the village itself I did gain a third Vulture sighting for the trip.

So what of the trip targets that I didn’t gain? Barbary Falcon was always likely to be the most difficult, requiring I suspect a knowledge of territories in remote upland locations. Plain Swift arrives mainly from March though some are said to over-winter. And I doubt if there are as many Laughing Dove on arid Fuerteventura as perhaps other Canary Islands. Well those are my excuses anyway!

Conclusions

Well organised and fully informed birders could probably cover Fuerteventura in three days. The passerines are easy to see pretty much anywhere, and it is worth noting that of the 9 lifers I gained on this trip 5 were close to my chosen base. I had good to excellent views of the most important birds, if only once or twice in some instances. But all it takes is one published report of Houbara Bustard walking across the road in front of one observer for that to become the expectation, and life and birding “ain’t like that, is it?”.

The mass-market ambience of Caleta de Fuste was a trade-off for me, but a necessary one since the all-inclusive package at my bearable but rather tacky hotel catered for all my sustenance needs. And I was pleased to have made friends with other birders there. On returning home, as usual what I recall from this trip is the wildlife and fabulous scenery experienced, and that translates into a warm glow until the next one wherever that might be.

Southern Portugal: 6 – 26 January 2014

Eastern Algarve and Baixo Alentejo

This was my second visit to the area following a 10-day taster in the concrete jungle of Albufeira 12 months previously. This time I chose as my base Tavira at the eastern end of the Ria Formosa, because it is picturesque and characterful by Algarve standards and retirement market holiday specialist Mercury Direct’s best value package also happened to be there. It was an hour’s drive to the coastal reserves west of Faro, so I chose not to go further west than there. Inland to the Vale do Guadiana natural park and Castro Verde SpAs took a little longer, depending on my route.Tavira marsh

Turismo de Portugal’s pdf Birdwatching Guide to the Algarve, that I used as my basic reference for this trip, lists three birding sites (A, B and C) around Tavira. On setting out to explore it became clear that all of these were around 20 minutes walk from the town centre. I therefore decided to defer hiring a car until I had done the local area justice on foot. All of the regular west European waders, by which I mean those not considered scarcities in the UK, winter here in huge numbers.

Site C: Santa Luzia (western) marshes – I visited this site first on 6 January since the pdf guide describes it as the best for Audouin’s Gull. That species was a major trip target since I hadn’t found it anywhere in the Algarve a year earlier. From a housing estate on the western edge of Tavira, a dirt road leads out from Rua da Santo Antonio to a large salt works where the gulls are said to perch on the walls of the salt pans. I didn’t see any at the mid-afternoon time of my visit, but encountered an array of waders (notably Greenshank) and herons that would burst out of ditches as I came near, other gulls and various small birds. On the walk back I wandered out into the marsh along tracks between the worked out salt pans, and found this trip’s first Caspian  Tern amongst the increasing numbers of birds that were coming in with the tide.

Tern amongst the increasing numbers of birds that were coming in with the tide.

I revisited this site on the afternoon of 19 January, approaching from the village of Santa Luzia itself. Arriving at around 2pm I again checked the salt works for Audouin’s Gull but once more it seemed like the wrong time of day. Little Stint were present here amongst various small waders. Walking along the track towards Tavira then out through the salt pans, I found more marsh to explore (left) and by 4pm it was filling up with roosting waders and gulls, amongst which I did pick out five Audouin’s.

Site A: Forte do Rato and Arraial Ferreira Neto (eastern marshes) – On 7 January I thoroughly explored this area that I visited by car during my January 2013 trip. The road into it runs from a  junction beside Tavira’s main shopping centre, and after a short distance the tracks out into the salt pans begin (right). Stand out Mediterranean species like Black-winged Stilt, Greater Flamingo, White Stork and Avocet were all immediately apparent, along with Common Sandpiper and small birds such as Zitting Cisticola, Sardinian Warbler and Serin.

junction beside Tavira’s main shopping centre, and after a short distance the tracks out into the salt pans begin (right). Stand out Mediterranean species like Black-winged Stilt, Greater Flamingo, White Stork and Avocet were all immediately apparent, along with Common Sandpiper and small birds such as Zitting Cisticola, Sardinian Warbler and Serin.

Re-joining the road, I walked out as far as it was possible to go, to the mouth of the Ria Gilão by the Ilha de Tavira, where there were a good variety of common waders and numbers of Sandwich Tern, but no Audouin’s Gull. On the walk back, the trip’s first Iberian Grey Shrike (right)  allowed me to walk right up to and under its overhead wire perch. This bird was in exactly the same place when I passed it again on 17 January. On that rainy day I also found a lone Slender-billed Gull on the beach at the end of Arraial Ferreira Neto, another species that had eluded me a year earlier.

allowed me to walk right up to and under its overhead wire perch. This bird was in exactly the same place when I passed it again on 17 January. On that rainy day I also found a lone Slender-billed Gull on the beach at the end of Arraial Ferreira Neto, another species that had eluded me a year earlier.

Along the river through and just north of Tavira town centre on different days, I noted various waders including Redshank, Grey Plover and Green Sandpiper.

Site B: Sitio das 4 Águas (central marshes) – First visited on 8 January, this was the most productive of the three birding areas in the pdf guide, though being there at high tide probably helped. From the town centre a road leads below a concrete flyover and out to the mouth of the  Ria Gilão on the other side of the estuary from site A. After drawing blank on the two previous days, I had a hunch this would be where I would find Audouin’s Gull. At the first big salt pan I came to, where the road bends sharply to the right, I recognised one flying in to join a group of several others. I could see at once they are unlike any other gull (left), absolute beauties that I immediately installed as my personal favourite gull species.

Ria Gilão on the other side of the estuary from site A. After drawing blank on the two previous days, I had a hunch this would be where I would find Audouin’s Gull. At the first big salt pan I came to, where the road bends sharply to the right, I recognised one flying in to join a group of several others. I could see at once they are unlike any other gull (left), absolute beauties that I immediately installed as my personal favourite gull species.

I then went out to just before a quay on the Tavira channel between the marshes and the Ilha de Tavira, where a dirt track led westwards. With the sun low behind me over the island, I could scan inland in a superb light and it was teeming with bird life. Huge numbers of waders were either feeding or roosting in the flooded salt pans, with both Godwits well represented and lots of Ruff. An impressive group of Spoonbill and some Spanish Sparrows were also noteworthy. At the end of the track a narrow path led further into the marsh as far as an un-crossable creek, the other side of which was Santa Luzia marsh (site C). I sat on a rock to rest and watch, and an Osprey passed overhead out towards the island. At 10:50am an interesting procession passed along this creek of swimming Cormorant and flying Egrets, Spoonbill and Sandwich Tern; all moving out towards the Tavira channel together. I realised that the birds were leaving the marsh and started to walk back soon afterwards.

The salt pans were now less populated, with waders feedig on the exposed mud of the channel,  amongst which I picked out numbers of Knot amongst the Ruff. Back at the start point two Caspian Tern (left) were loafing amongst the Gulls, and seven Audouin’s were still there dozing the day away. I stopped by at this spot, that is opposite a derelict mill with a tall chimney, several times during the rest of this trip. Audouin’s Gull were always present in varying numbers, with around 50 birds present on 17 January.

amongst which I picked out numbers of Knot amongst the Ruff. Back at the start point two Caspian Tern (left) were loafing amongst the Gulls, and seven Audouin’s were still there dozing the day away. I stopped by at this spot, that is opposite a derelict mill with a tall chimney, several times during the rest of this trip. Audouin’s Gull were always present in varying numbers, with around 50 birds present on 17 January.

On 26 January I came back to Quatro Águas for a final look around. There were plenty of Audouin’s Gull and two Caspian Tern roosting again. As I walked out to the quay the Osprey was sitting on a telegraph pole surveying the scene. Then on the small path off the track from the quay and out to the creek, a female or first winter Bluethroat jumped up and posed close in front of me, a perfect sighting with which to end the trip. This bird then flew back along the path a little way and walked ahead of me with tail cocked as I followed it. Along the return walk to town. the Osprey was back on its pole eating a fish.

Cerro do Bufo area of Castro Marim wetlands

After that thorough 3-day exploration of the Tavira marshes on foot, I decided to do the next two nearest sites by public transport. On 9 January I chose the closer option travelling by the coastal rail service to Vila Real de Sto António, where the station was about 20 minutes walk from the Castro Marim marshes. With Audouin’s Gull already seen, there was no particular purpose to this visit; I just remembered having enjoyed going there a year earlier.