My personal third new Warbler nationally of this early summer, and second life list addition in that group, was possibly the most welcome of all. Each season I read of Blyth’s Reed Warblers at reasonably accessible coastal locations, but had not opted to go after one before this. Now a mere 80 mile excursion along the old corridor to excellence that is the M40 and M42 was at last a tempting opportunity.

That previous reluctance to convert the lifer mostly arose from a perception of this bird as “difficult” to distinguish. Given my aversion to plumage topography I had thought it is perhaps best told apart on song, which is totally different from regular Reed Warbler and very varied involving much mimicry of other birds. So I was concerned to travel with a day’s colleague who had experienced the species before and knew how it sounded. Hence I met Ewan at his home in west Oxon at 7am and off we set.

The former gravel pit complex of Middleton Lakes (SP204998) being another RSPB reserve, I wanted to arrive ahead of the day’s bless ’ems. But this not being a lifer for my companion there was no need for a dawn twitch, which suited me. When we reached site at 8:30 it was plain from the number of vehicles in the car park (B78 2AE) a lot of green clad optics carriers were there ahead of us. Indeed Ewan showed me pictures that had begun to appear on Twitter some four hours earlier.

We strode out on what seemed a very long walk through this vast and sprawling reserve, eventually catching up with the twitch group at the spot described on the bird information services, which lies just across the Warks county boundary with Staffs. What a relief it is that nobody really bothers to distance any more, as was also true of the other recent twitches recounted in this journal. I could hear the song researched earlier on Xeno Canto (see here) issuing from the Willow of the RBA posts as soon as we arrived, and it didn’t take long for the Blyth’s Reed Warbler to show itself.

Over the next three hours or so the bird remained faithful to more or less the same singing perch in the Willow (pictured above, right), rarely posing openly as in some of the published early morning pictures, and mostly keeping partially obscured. My thanks are due to Ewan for providing the images for this post, as I stood no chance with my own camera on this occasion. Throughout the songster poured forth it’s full repertoire that I found an uplifting experience, and it’s jizz was to my mind always pleasant and understated.

The contrast with regular Reed Warbler was such that I wondered why a more appropriate name had never been found for the entity I was now witnessing, especially since this species is not attracted to reed beds or waterlogged ground but breeds in deciduous growth along rivers. On looking him up and not wishing any disrespect, Edward Blyth (1810 – 1873) worked as a curator of zoology at the museum of the Asiatic Society of India in Calcutta. At least 12 bird species and a number of reptiles still bear his name, including also Blyth’s Pipit (see here) that occurs regularly as a national vagrant. As with some British dragonfly names, I personally would prefer these historical Victorian anachronisms to be moved on from.

As things turned out today the whole experience of gaining what I had thought of as a difficult lifer was actually quite straightforward. Warbler twitches so often involve staring at banks of vegetation for hours on end to catch glimpses of skulking quests. But this bird stuck to a readily viewable location singing all the while, and so put on quite a show. I now realise the misnomer in question bears virtually no similarity to Reed Warbler not just in song but also its appearance, movement and habits.

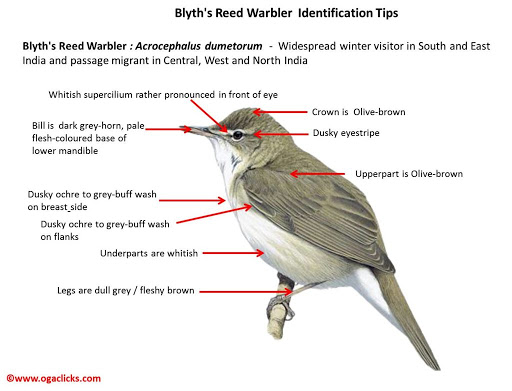

Where its diagnostics are concerned Blyth’s is described as being a little smaller and less robust than Reed Warbler, with a more rounded body shape; and shorter-winged with a short primary projection. The bill is weaker, finely pointed and distinctly spiky; and the legs are also slighter. The Helm guide to confusion species also cites BRW’s plumage as overall greyer and lacking any rufous tones to the rump, while the underparts are silky white with some buff toning. This illustration (below) presents the required detail.

The species winters in south Asia and breeds across north-eastern Europe from the former “Baltic states” eastward through Russia and Siberia. British records, in May and June with a larger autumn peak in late September and October, are said to be increasing from a historic median of around eight a year. Most occur on the northern Scottish and Scilly Isles, with some on the east and south-east coasts of England. So to observe this much sought lifer at such a convenient inland location as today’s was exactly the kind of opportunity I seek.

Going into this quite strange summer with a limited wildlife agenda comprised mainly of insects and reptiles, I could not have imagined gaining such life and British bird list additions as River, Blyth’s Reed and Great Reed Warblers within 15 days of each other. In the ongoing climate any further gains that do not involve travelling abroad will of course be more than welcome. Sooner or later things do turn up within range and I remain ever hopeful of more. There are now as many birds on my British list as days in the year … 365.