As well as it’s triple-lifer potential this trip also offered scope for observing some iconic birds – Diver, Grebe and Phalarope – in their full and colourful breeding plumages, that only pass through southern England on spring migration. After the previously recounted Harlequin adventure, I moved on to the Mývatn visitor centre at Skútustaðir (see here) on the lake’s western edge. There, with the aid of substitute binoculars loaned to me by the rangers, I realised more of those desired experiences.

This Red-necked Phalarope (above) was the trip’s third stand-out close encounter, together with the subjects of the previous two posts. I had never observed a female in full breeding plumage until now. Like my three past Oxfordshire encounters – at Farmoor Reservoir (Nov 2013 and Sep 2017) and a male at Bicester Wetland Reserve (May 2015) – this individual fed with quick picking actions before me, moving busily forward as it did so and needing to be chased. The feeding technique is often by spinning in the water as I recall from an older record at Farlington Marshes, Hants (Oct 1987).

RNP is a fairly frequent May and June Icelandic breeder in wet marshes or pools such as here, where they nest in the tundra. Unusually, the less colourful males incubate the eggs. This population departs from early July to lead a pelagic life off the coasts of west Africa. Grey Phalarope (known as Red Phalarope in north America) is far less common in Iceland and does not usually occur at Lake Mývatn.

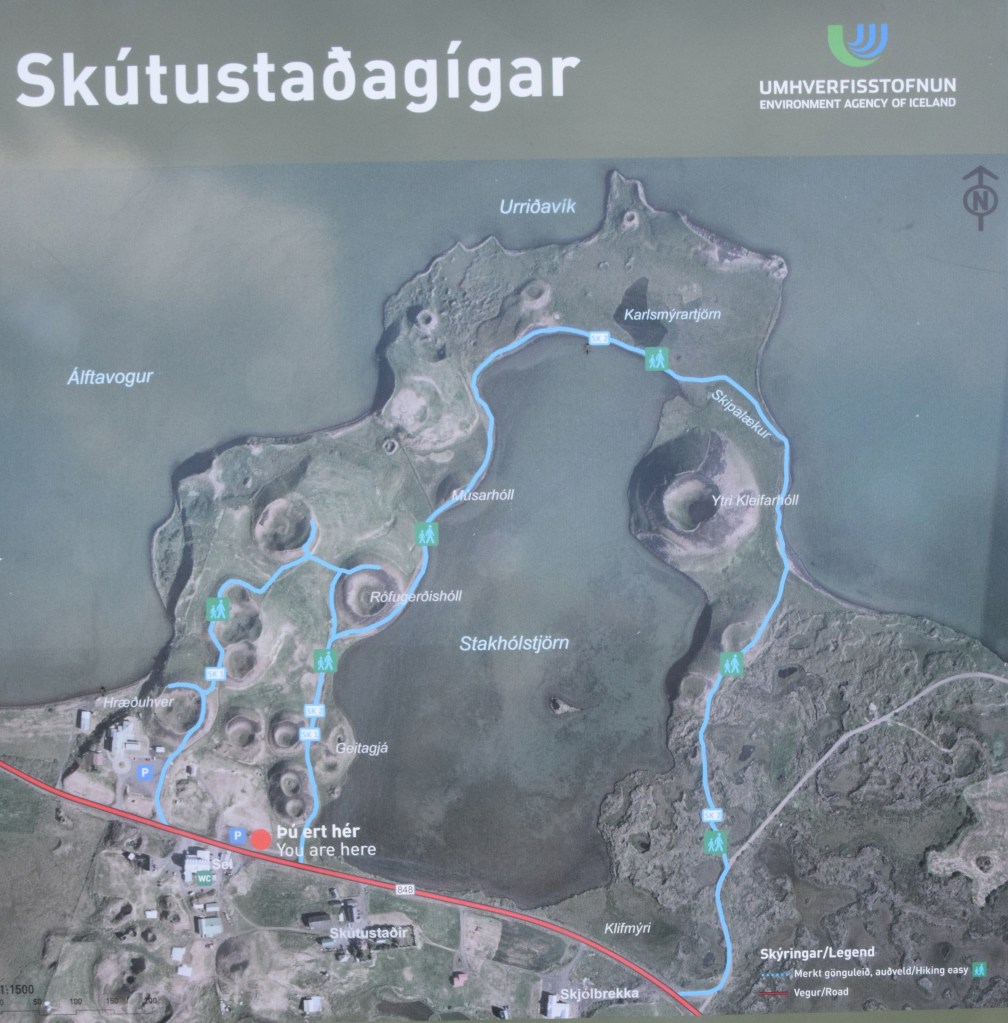

The visitor centre is situated amongst a cluster of craters (below), adjacent to an enclosed lagoon, Stakhόlstjörn that is cut off completely from the vast water body of the lake itself. A 2.3 km trail, from which the birds now presented were all observed, runs around the area.

Slavonian Grebe is the sole species of its group to breed in Iceland, and is common only at Lake Mývatn. The now modest population is in significant long-term decline for reasons that are not fully understood. These birds winter on north-western European coasts, though a few may linger along the southern coastline of Iceland itself. I came across them in a number of locations during this trip, and several at this site. As at Farmoor Reservoir earlier in the spring (see here) their dark, bright colouring in prevailing glare didn’t aid the cause of picture taking. The following records are the only two I kept from many attempted.

Slavonian Grebe

Long-tailed Duck, Scaup and Common Scoter all breed here, and I crossed paths with the threesome around Stakhόlstjörn. The first of those has an estimated breeding population of between 2 and 3000 individuals at Mývatn and across northern Iceland. Wintering numbers, swelled by migration from other regions, are in excess of 110,000. The other two ducks will be dealt with in the next post.

Long-tailed Duck (record shots)

Arctic Tern arrive here at this time of year and remain until August. Since I am used to recording that trans-global migrant only when passing through southern England on their progress northward, it was now quite exhilarating to watch large numbers of the elegant and graceful item hawking for the super-abundant midges over the lagoon’s surface. Such sights only occur at my local Farmoor Reservoir when birds passing high overhead are driven down by foul weather, and usually involve a drenching. All the Terns in Iceland are Arctic.

Arctic Terns

Earlier in the day I had located another summer plumaged trip target Red-throated Diver at Laxárdalur, upstream from the rapids. The Icelandic breeding population is estimated at between 1500 and 2000 pairs. These birds mostly bond for life and re-visit the same nesting locations year upon year. The bulk of them winter in western Europe, though a small, sedentary population remains on the south-west coast. This (below) was my first ever record in the breeding plumage. Iceland’s other summer Diver, Great Northern or Common Loon, was one of two wish-list items that I failed to convert; the other being Gyrfalcon.

The Skútustaðagígar pseudo-craters are not magma-producing volcanic vents but were formed around 2300 years ago when molten lava from two nearby eruptions flowed over cool, wet surfaces here and pressurised the earth downwards. That trapped steam under the weight of the lava, and when the pressure became too great explosions were triggered creating depressions in the ground. The largest of these features is Ytri Kleifarhóll, on the lagoon’s eastern side (slide show picture 2); and for me the most imposing is Rófugerðishóll (picture 3). A smaller cluster closest to the visitor centre itself rather resembles a golf course as viewed from the road (picture 4). To my mind this landscape has a peculiar scenic allure that has formed a lasting impression, hence its inclusion herein.

This was a very rewarding and enjoyable few hours at what was the week’s best Mývatn location in which to connect with this post’s various described birds. And by the time of publication my binoculars had been repaired under warranty by the manufacturer, Opticron.

NB If visiting this site be sure to use insect repellent on all exposed skin